It’s the end of the week which means its the end of my series of throw back interviews. I don’t want to say I’ve saved the best until last, but I definitely think this was the interview I was most excited to get to do.

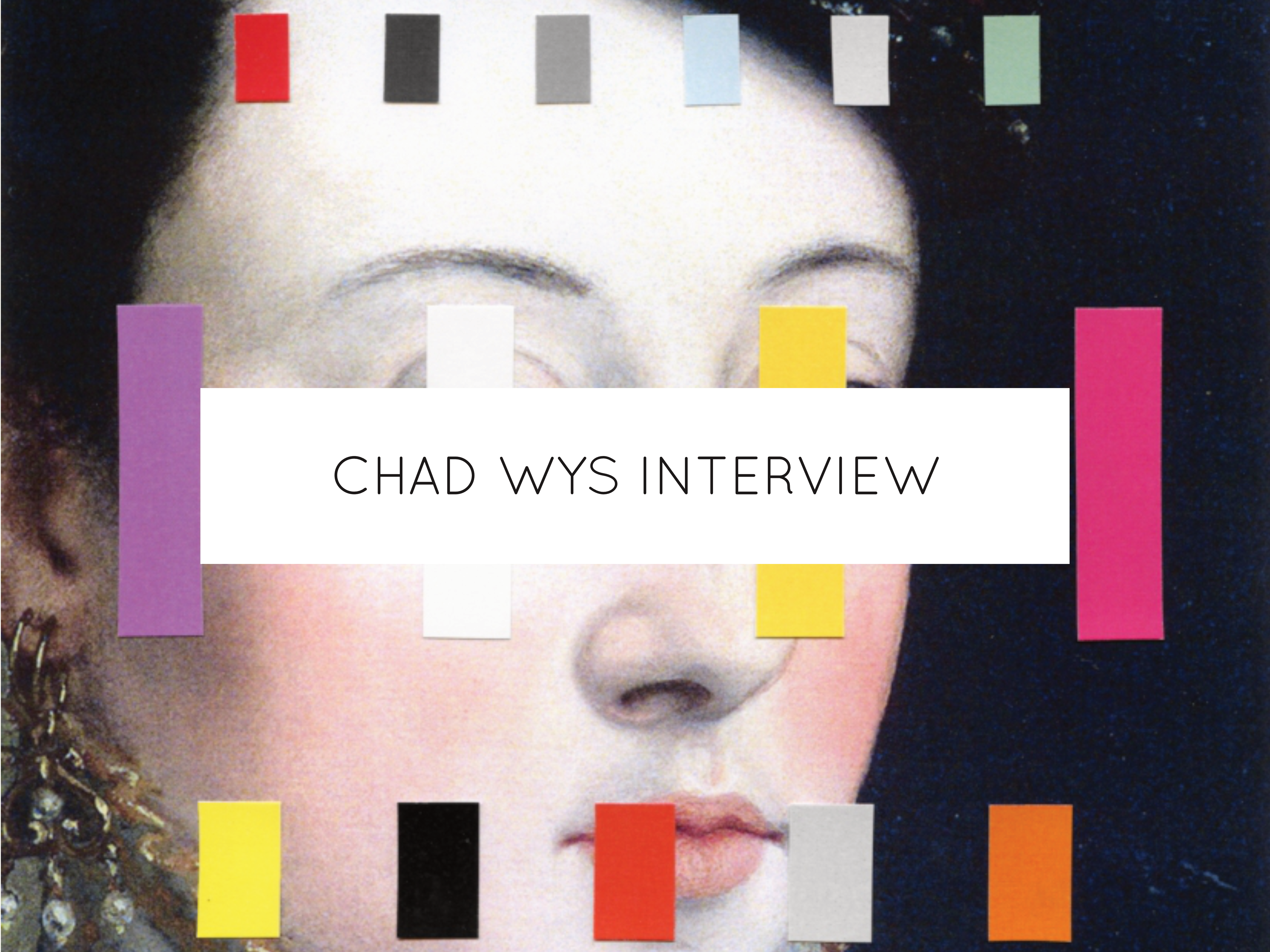

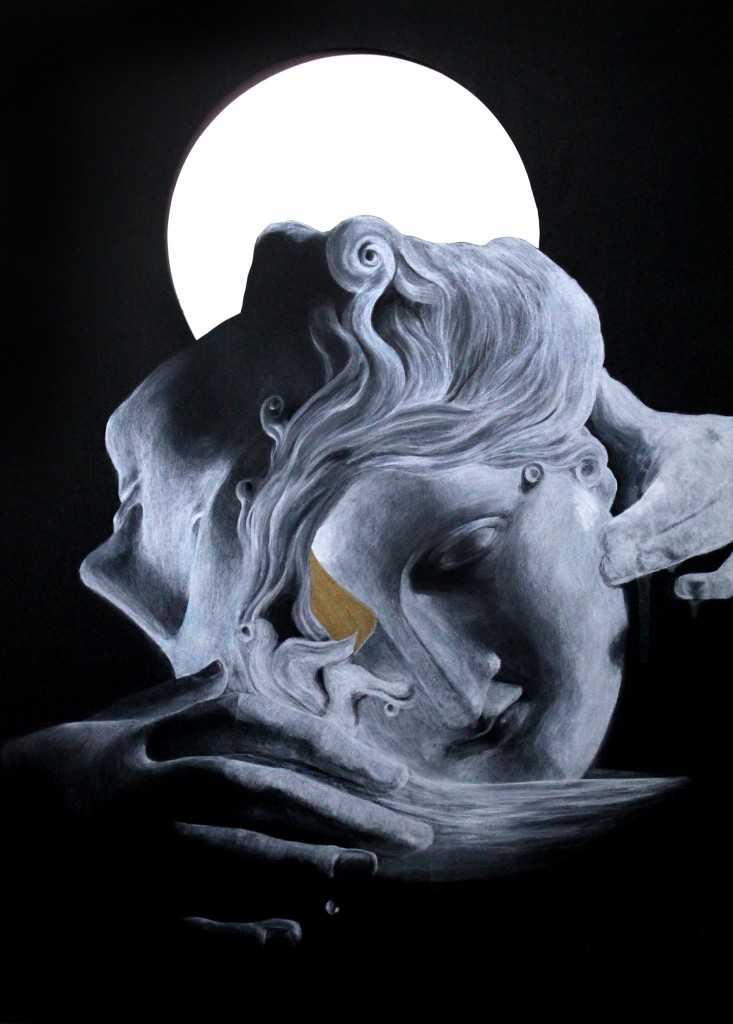

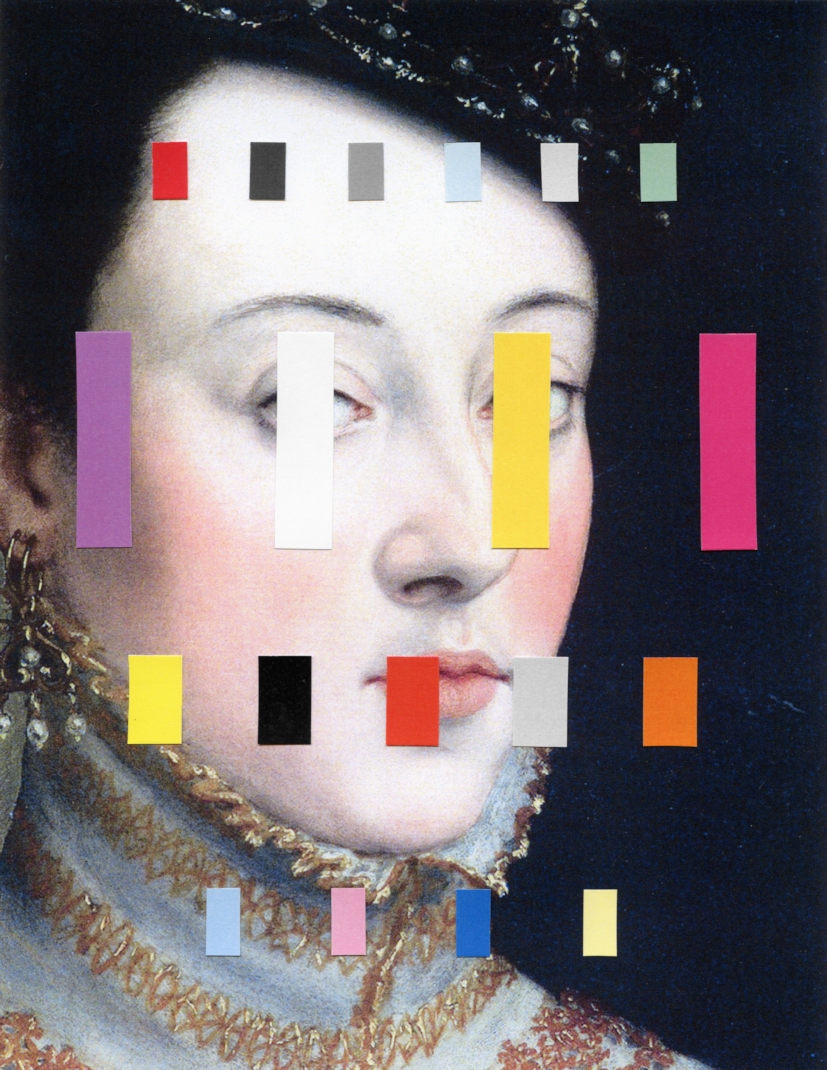

PORTRAIT WITH A SPECTRUM 4/CHAD WYS

Chad Wys is one of my favourite contemporary artists. I tried to start this article with something that sounded more professional than that, but I thought I should just be honest. His work is conceptually focused without being aesthetically compromised, it’s approachable without being dumbed down, and it’s fun without ever lacking gravitas.

After Wys completed Masters at Illinois State University, his studies in art theory, criticism and philosophy led to an interest in conceptualism, minimalism and the postmodern as well as the idea of “objecthood”. A major theme in his work, “objecthood”, for Wys, covers questions of “how we decorate our lives with arbitrary as well as meaningful things; how we objectify the ones we love and the strangers we see; how we objectify pain and death; how we objectify complex and sensitive cultural histories.”

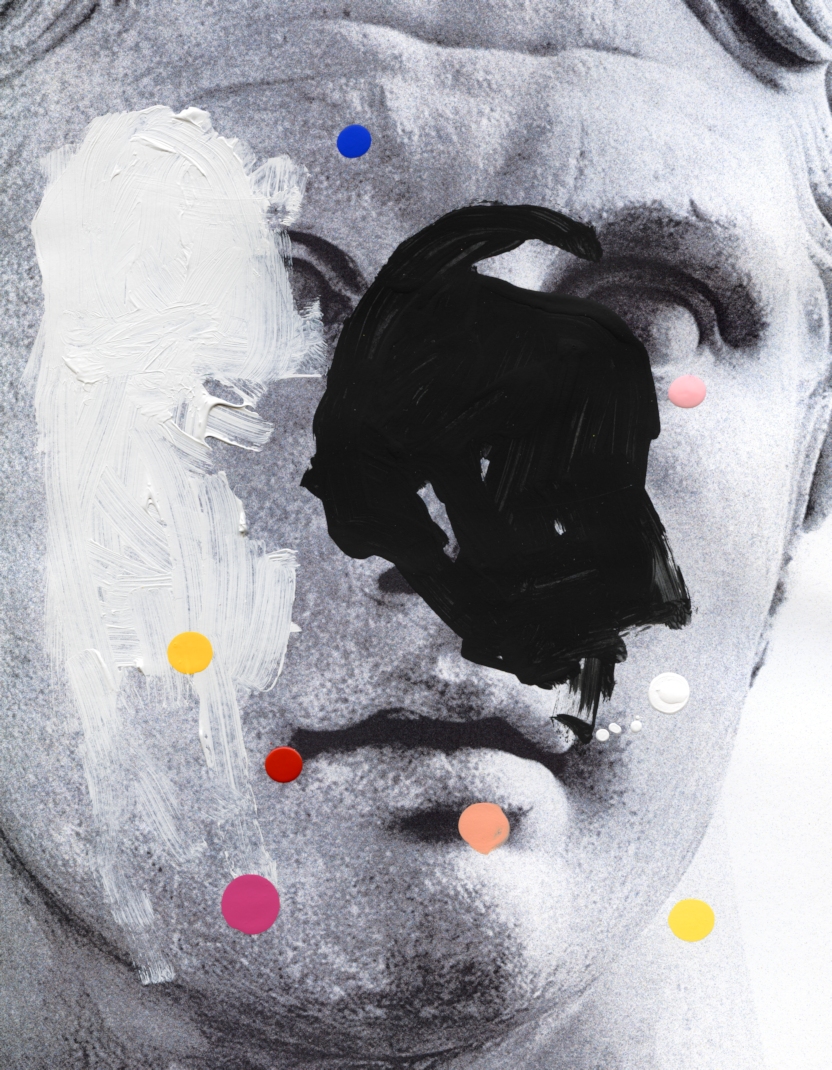

CAUTION GOYA/CHAD WYS

Although he describes himself as an “apprehensive artist”, the immediate impact of his adept use of colour and form mean it’s hard to imagine his skill going to waste. When working canvases of readymade works Wys either commits to a completely complementary or a caustically contradictory colour palette. The “aggressive” addition of foreign colour to the familiar, is Wys’s way of creating new meaning from the ensuing tension between ‘paint’ and ‘canvas’. This satisfying visual disharmony is a form of destruction in its own right, asking the audience to question their own response to reviewing a reclaimed object. It is the erection of these barriers of colour “between the viewer and the object through which one must negotiate an understanding of what is both present and hidden” that Wys sees as his “distinctive vocabulary suitable for not only sharing ideas but provoking serious deliberation in the viewer”

“Sure, I’ve got some ideas I want to get across, and aesthetics will always be my main tool for doing just that, but it’s out of my hands by the time it gets to you.”

His most popular pieces feature reproductions of images like those he saw in the “picture books devoted to 19th and 20th century painting” that captured his imagination at a young age which have been reworked and reimagined. In his choices of media Wys experiments with mixing the technological and the traditional with a view “to blur the boundaries between the material and the digital”. This range of visual sources, styles and suggestions make the audience unquestionably aware of the reappropriation at work in front of them. Consequently, the marks that Wys leaves on these readymades can’t help but to instantly evoke images of “R.Mutt 1917” signed on a urinal in their sentiment and often their line quality. These acts of applying contemporary ideas and marks to objects from the past plays with ideas of social constructs, meaning and influence. Wys strikes up this multifaceted conversation with the viewer to engage them into considering their own conceptions of object ownership as a marker of both social and self worth.

“When people get angry at me for “stealing” and/or “vandalizing” another artist’s “hard work,” they unwittingly underscore the complex web of problems at play in our visual world, since, really, I’m doing nothing of the sort; quite the contrary in most cases, I’m pointing out that the original was “vandalized” the moment it was reproduced”

Additionally, Wys only works on mass reproductions of works further raising questions of both image ownership and what it truly means for a work to be an original, especially “in the age of the Internet reproductions, which are now digitally transmitted instantly and endlessly, are more present and more malleable than ever.” Wys warns us as observers to “be as vigilant as ever to distinguish between aesthetics and context, form and function, and the re-presentation of likenesses and the disassociation from referents.”

“Processing “life” and art through a screen requires a good deal of adaptation, as does presenting one’s “life” and one’s art through various screens. I choose to look at that sort of adaptation as an opportunity, not a compromise.”

But, ultimately, what lies in Wys’s work is entirely in your hands as “in the end as in the beginning [he is decidedly postmodern leaving] the activity, reception, and understanding of my work entirely in the viewer’s hands.”

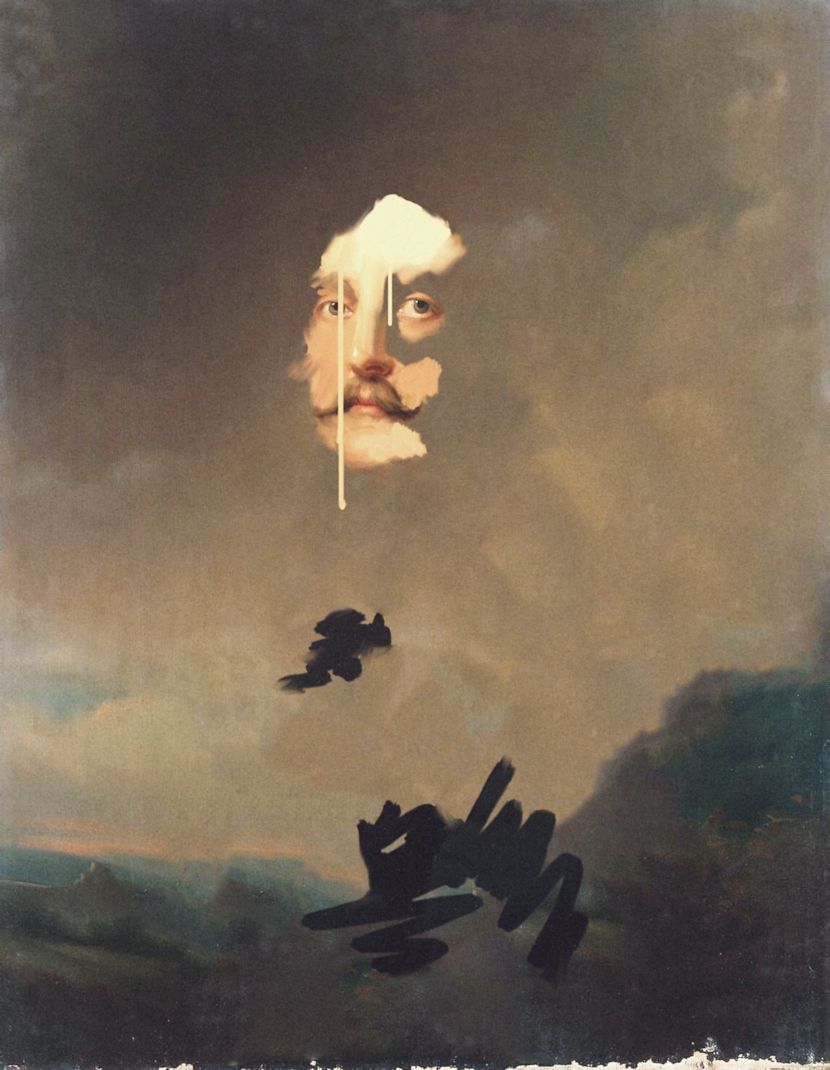

GARAGE SALE PICTURE OF AN ENGLISH OFFICER/CHAD WYS

You’re currently on Twitter, Tumblr, Behance, Society6, Etsy and you have your own website. Why did you feel it was necessary to cover so many different social media outlets, is it a case of simply ‘getting your name out there’ or do they serve different purposes for you?

Don’t forget the behemoth: Facebook. Superficially, each platform is suited to different modes of information, and so they cause people to interact differently even with identical content. The same people can follow me on each platform but expect a different level, or style, of engagement from each. For example, I’ve found that the casual thoughts I tend to Tweet don’t go over quite as well on Facebook or Tumblr (Twitter being a space for short, subtle observations), and the images I share aren’t generally as effective on Twitter as opposed to a visually-rich platform like Tumblr.

To a large extent proliferating out onto multiple social networks is an effort to be seen and read by as many people as possible, what is your motivation behind gaining an audience?

Networking and name recognition has never been a goal of mine, and it still isn’t. Primarily, I enjoy the process of communication and I enjoy aspects of the different ways of interacting that each of the these platforms provides. Ultimately, I see some value in sharing my thoughts and creations in this way. There are still more platforms for me to try and still others I’ve determined aren’t as useful. However, I think one ought to use these tools responsibly because drowning in the deep end of narcissism is easy.

More and more artists today are putting their work online, do you think an online presence is essential to being a successful (commercially or otherwise) at present?

I doubt it’s essential. The art world still seems to be dominated by the politics of collecting and selling and the influence of subjectivity from a select few, which still seems to originate in particular real-world, geographic hubs like New York, London, LA, et al. But I think being technologically-present, -aware, and -fluent will always be useful, especially for communicators such as artists (and especially for emerging artists).

It’s obvious that the Internet is not a fad and that it’s only the most powerful communications tech the world has ever known. An artist who doesn’t wish to exploit that premise is, for whatever reason, proactively invested in preserving traditions of the past. That’s their prerogative and I certainly won’t judge them harshly for it; there are good reasons to base one’s practice and the reception of one’s work in the material world. However, I think the Internet is so pervasive and so utterly powerful that it has become the norm. To not have a portfolio website and to be a visual artist is to be a kind of “off-grid rebel,” or you’re someone who hasn’t caught-up, or you’re someone who’s made a particular set of choices that exclude the massive elephant in the communications room, or you’re so well-liked by the correct art world elite that you don’t need to do much of anything to assert yourself.

The advantage to being an Internet-present artist is fairly clear: access to a virtually unlimited audience; while the disadvantage is also fairly evident: there’s practically infinite noise in which to get lost, and the noise is chaotic and difficult to overcome on one’s own terms. Adaptation is a prerequisite to using the Internet and especially social media. I can understand why some would not be willing to adapt to tech systems of this sort because that can easily be construed, and I think often wrongly so, as compromise. You’ll have to ask someone who avoids the Web why they do so, but you’ll have to dig up their phone number or unearth their street address first (maybe that’s the advantage!).

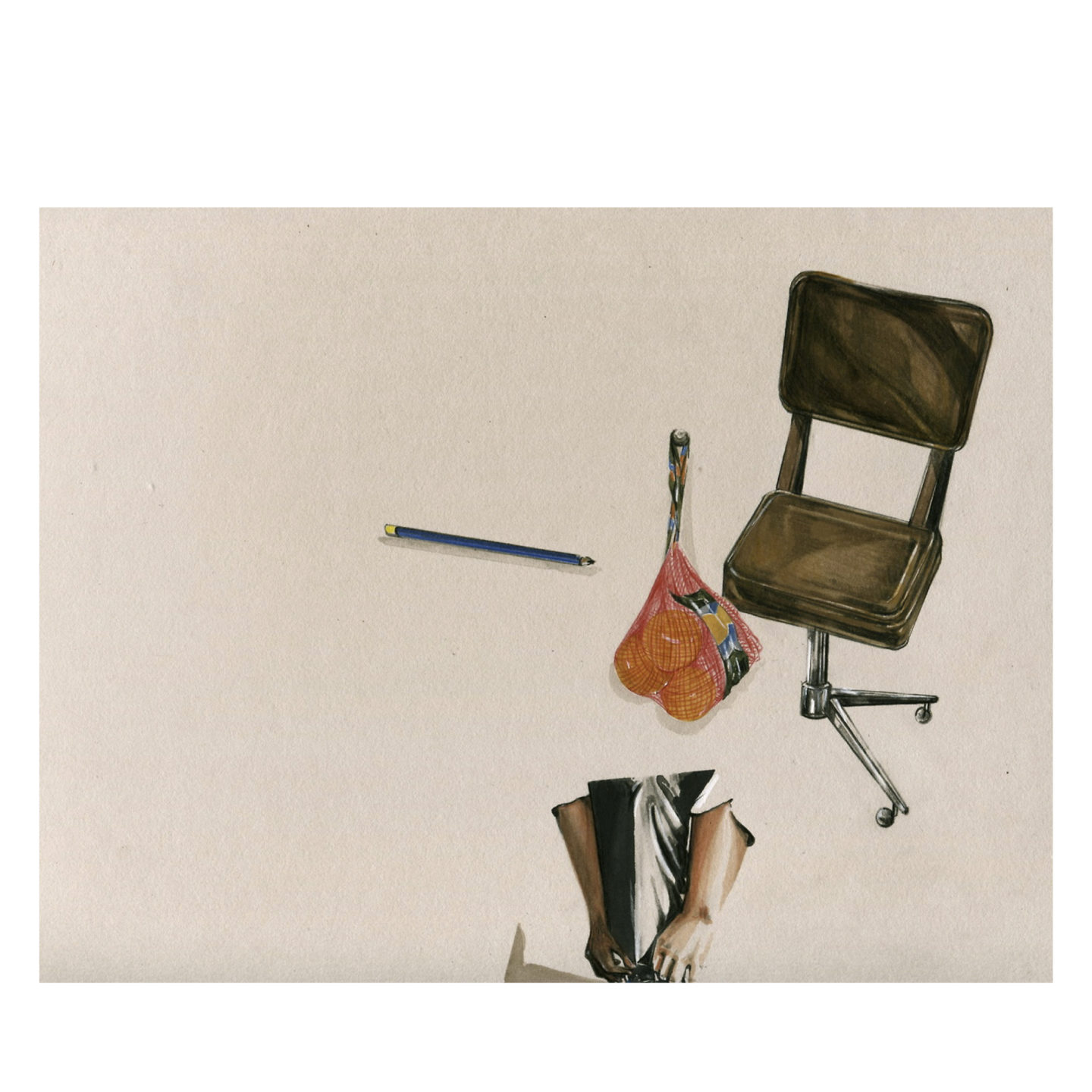

COMPOSITION 476/CHAD WYS

You refer the internet as “the most powerful communications tech the world has ever known”, I was wondering if you feel like there’s a dialogue then between you and your audience, for example the people you mentioned being angry you use of other works? And if so, how do you feel that dialogue informs you or alters you perspective or is even part of your work?

There’s certainly some dialogue there, and there’s always potential for more. That’s part of what draws me to the Internet: it can be as “one-sided” as a typical gallery show, or it can spur on engagement with people from any corner of the globe. The folks who react vehemently to my work generally aren’t up for a debate; much of the time they’ve made a series of determinations about what I’m doing, and that’s that. I’ve engaged with a few of them over the years–either they have contacted me directly and opened up a line of communication or I’ve found their public comments and I’ve engaged. Whether or not they’re receptive in the first place has a bearing on how constructive the dialogue becomes; though I often find that people who are receptive to new and different ideas aren’t likely to resent my work. But these dialogues do happen. The key is not to get involved with arguments where I am, for example, put in the position of defending all that is, ever has been, and ever will be “art”… what a hopeless and uncomfortable spot to be in.

What do you mean by the “noise” of the internet? And what’s involved in adapting to online communication?

Well, adaptation can be as simple as learning to use 140 characters effectively on Twitter, or learning to edit one’s oeuvre down to a manageable size on one’s personal Website. One has to adapt to the tools one chooses to use, or one has to seek-out or invent new tools to fulfill one’s goals. Processing “life” and art through a screen requires a good deal of adaptation, as does presenting one’s “life” and one’s art through various screens. I choose to look at that sort of adaptation as an opportunity, not a compromise.

As for the “noise” of the Net: simply, there are a lot of us. My attentions are strained through my various information “feeds,” whether on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, or what have you. There is a lot of information, potentially limitless amounts, and it’s impossible for each of us to process everything. I think we can easily become desensitized to images, text, art, et al (not only online, but everywhere). It becomes necessary to process information differently and more rapidly and each of us grapples with that in our own way. It’s easy to gloss over an artwork to which one might otherwise deeply respond; it’s easy for one’s work to get lost in the shuffle of information, to be ignored, or to be shallowly received and unfairly dismissed. There are different solutions for overcoming the “noise” for different goals. I think the solution to being widely seen and perhaps even understood as an artist is to be present, persistent, consistent, and to create “good” work. But the better “remedy” for the social noise is to not expect to overcome it, and to not desire to overcome it; it ceases being an obstacle at that point.

In the statement on your website you say that “notion of object” is a major strand in your work, how would you say that “objectification” has been changed by the free availability of (quite often sourceless) images on the web?

That’s an important and sizeable question and it strikes to the core of my practice. My work generally grapples with art (history) and decoration/ornamentation and how we process our experiences of these things, so along those lines the game totally changed at the dawn of “the age of mechanical reproduction” (to lift a line from 20th century German modernist Walter Benjamin). Art’s “aura,” Benjamin argued, is dislodged, displaced, or diminished as reproduction is mastered and streamlined through advanced machinery. For example, viewers stopped observing the painting and started observing photographs of the painting, and in so doing lost a bit of the influence/experience/meaning of the original (for it’s no longer necessary to observe the enormous canvas and the vivid color palette of, let’s say, a Klimt painting since it has been reduced to a two-inch black and white illustration for rapid consumption).

Computers, and the ease of the anonymous digital imaging and text that you speak of, are simply (but complexly) a continuation of the industrialization of aesthetic and intellectual experiences that has coincided with the industrial revolution. I’m sympathetic but resistant to Benjamin’s notion that within each artwork there is an idealized “aura” waiting to be accessed by a special kind of recipient; that’s quite modernist and dated in its determinism. But I think the spirit of Benjamin’s cultural theory–which is that reception matters and is malleable through re-presentation–continues to be extremely prescient, and this is why I grapple with image- and object-based reproductions as my source materials: information is easily displaced and manipulated in the age of the Internet, so we have to be, as ever, vigilant and informed receivers. The marks I make on the particular materials I appropriate are my attempt to draw attention to the digital/mechanical outsourcing of experience… so by creating a new, modified experience through color and form, in my small way I’m trying to draw out the objectification, in some instances quite literally, of visual-intellectual experience. The Internet is a huge, glorious, and horrible part of this dynamic.

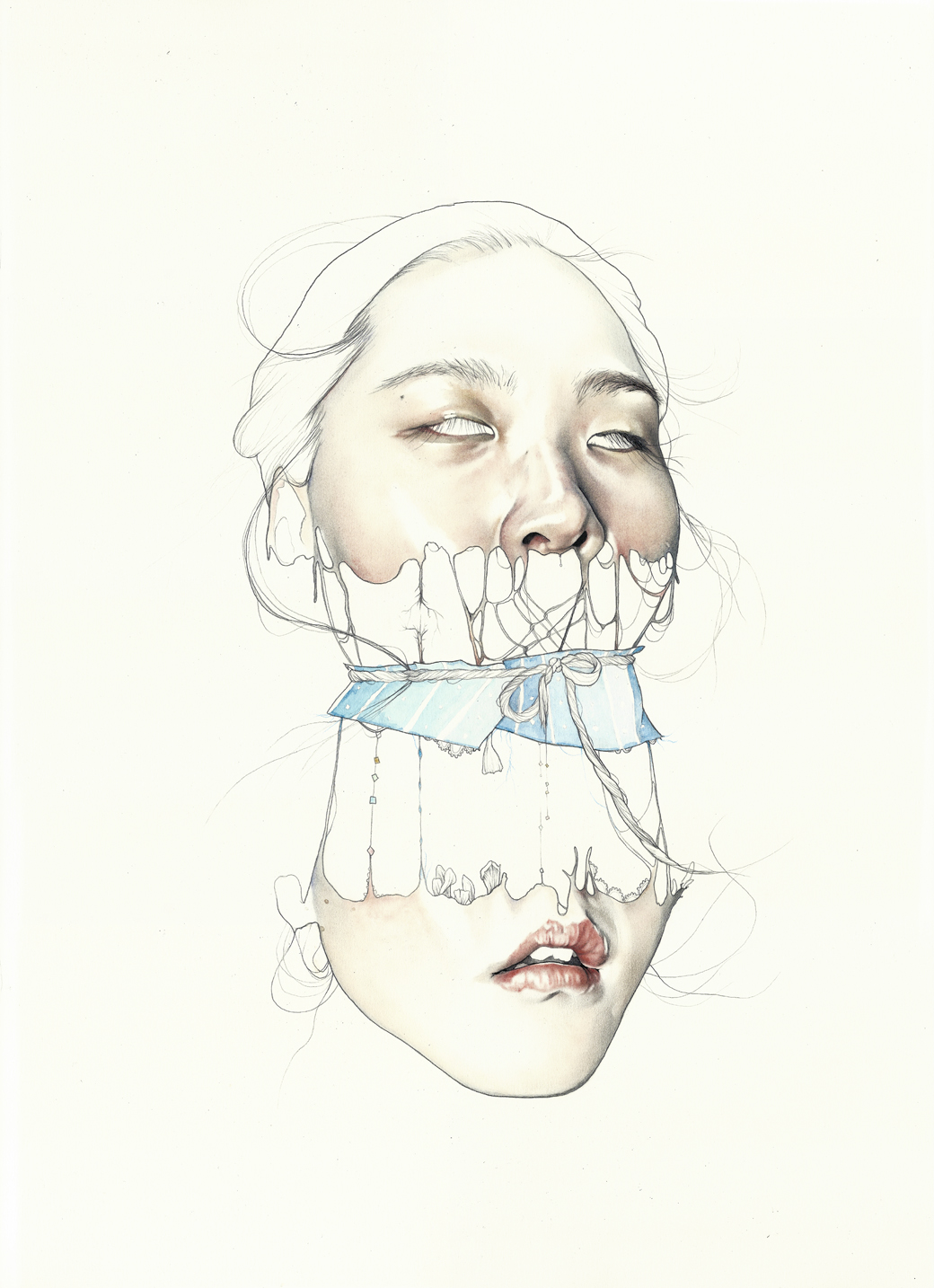

THE GIRL WITH STARS IN HER EYES/CHAD WYS

You also say that you “enjoy taking contemporary ideas into the past”, could it be said you are doing the reverse as well? As in your readymades you take older, quite often 19th century, pieces of art, rework them and then put them into a thoroughly modern context – the internet.

Yes, I think that’s true; certainly aesthetically speaking. But much of what I do, much of the material I source, is distinctly contemporary (or modern) insofar as the digital image I appropriate, or the factory-crafted copy of the Greek statue with which I’m interfering, or the mass-produced photomechanical print of a 19th century portrait that I’m re-purposing are of a time and of a context often separate and distinct from whatever originals these copies are referencing/mimicking/reproducing.

Broadly speaking, my work concerns the interplay between the aesthetic resonance of whatever image or object I’m sourcing, and that which the image or object literally is–which is often an inadequate transmission of the original, often several times removed by technology and through time. When people get angry at me for “defacing a Raphael painting,” that’s the dishonesty of their experience of the reproduction bubbling up, out, and over; they wind up defending the very process–the process of mass-reproduction–that so “endangers” the experience of the original that they ostensibly wish to protect. I’m quite interested in that sort of visual deliberation, or the deliberation of objectification. I want viewers to consider what it is I’m appropriating and why. When people get angry at me for “stealing” and/or “vandalizing” another artist’s “hard work,” they unwittingly underscore the complex web of problems at play in our visual world, since, really, I’m doing nothing of the sort; quite the contrary in most cases, I’m pointing out that the original was “vandalized” the moment it was reproduced (and that’s not a criticism of reproducibility more than it’s a criticism of our lack of consideration of reproducibility).

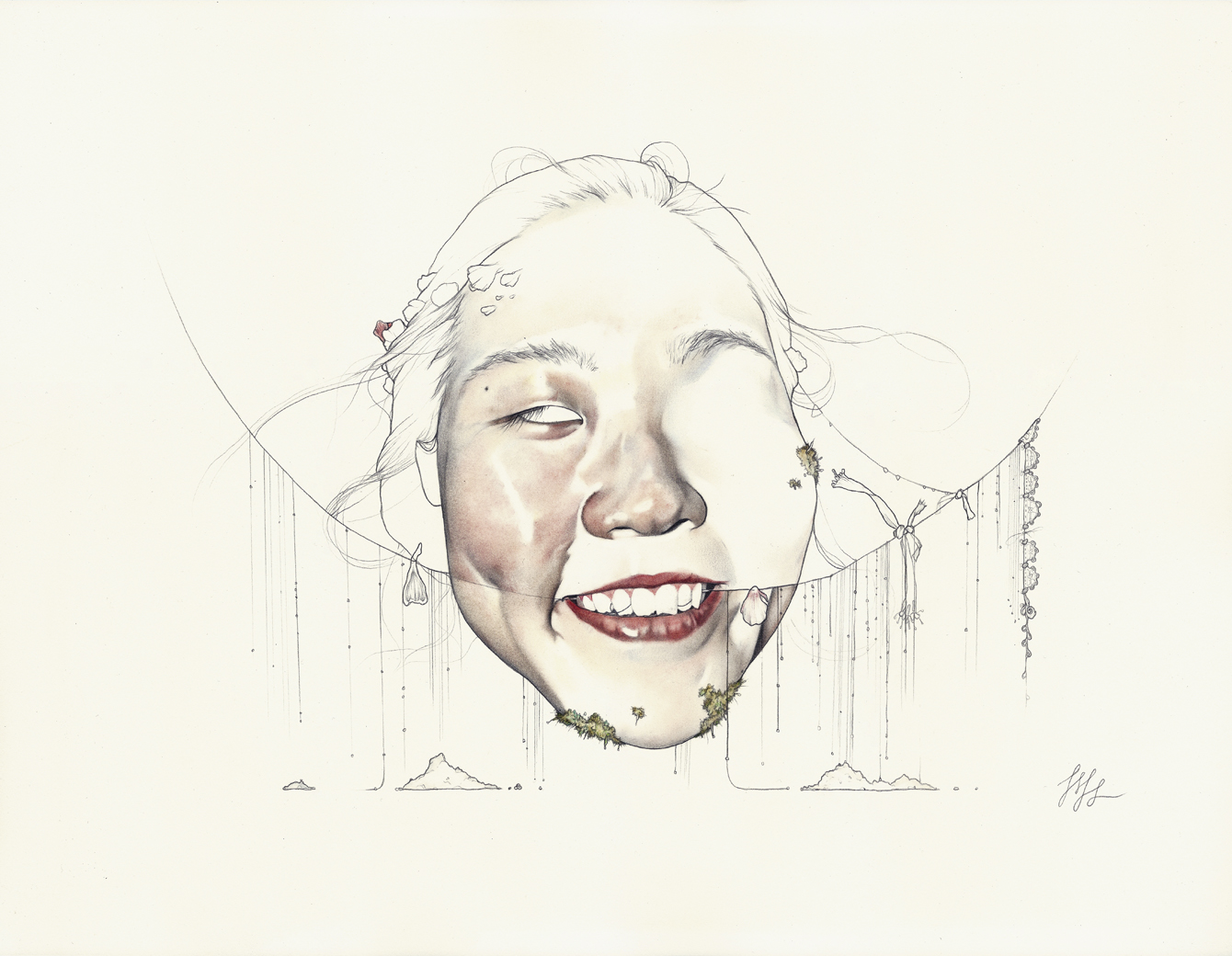

NOCTURNE 109/CHAD WYS

How much are the marks you make on works influenced by aesthetics versus making a specific point etc.?

I once heard that Franz Kline, the great abstract expressionist, used light projectors to plot out his bold, black paint strokes onto canvas. I’m not really interested in whether or not this’s true, but in my experience it could be. It’s difficult to instantaneously and instinctively execute a perfectly balanced minimal composition. It’s difficult to proportion a simple scene expertly and all of Kline’s compositions are expertly balanced. His paintings look and “feel” perfectly proportioned, despite (or because) the fact that they’re often just black strokes on a white ground. The reason why the light projector and the careful planning of the strokes could be seen by some as upsetting and detrimental is because abstract expressionist theory is so mythically built on the process of impulse… like an open nerve violently shooting paint onto the canvas. If Kline plotted out every brush stroke, some might view that as a nullification of the attractive image of an abstract expressionist at work: an artist putting every ounce of his or her raw brilliance onto the canvas in a rapid, divine, artistic orgasm.

The reason I tell this story is because the aesthetics of the mark and the purpose of the mark don’t seem very distinctive to me; well, they do, but not insofar as qualities should change depending on method or intent. Kline’s work represents the same things to me whether or not he carefully composed his compositions. My marks are the same intervention whether or not I have a point to convey or I’m going for a certain brand of color theory. How the viewer responds to the materials and the ideas I’ve put in front of them is all that really matters at the end of the day. Sure, I’ve got some ideas I want to get across, and aesthetics will always be my main tool for doing just that, but it’s out of my hands by the time it gets to you.

You can see more of Chad’s work on his website, tumblr, facebook, twitter and pretty much every other social media platform