I’ve been working more and more with colour recently, especially in my weekly patterns, which has forced me to really think about how I put together colour palettes. It’s something I’ve definitely gotten better at over the years, through trial and error and from trying to replicate colour schemes I like.

Here are some thoughts on how (after many failed attempts) I create a coherent colour palettes for whatever I’m making, whether that’s an illustration, a branding project, or picking out an outfit.

Before we get into how I put colours together, here’s a quick intro to colour theory.

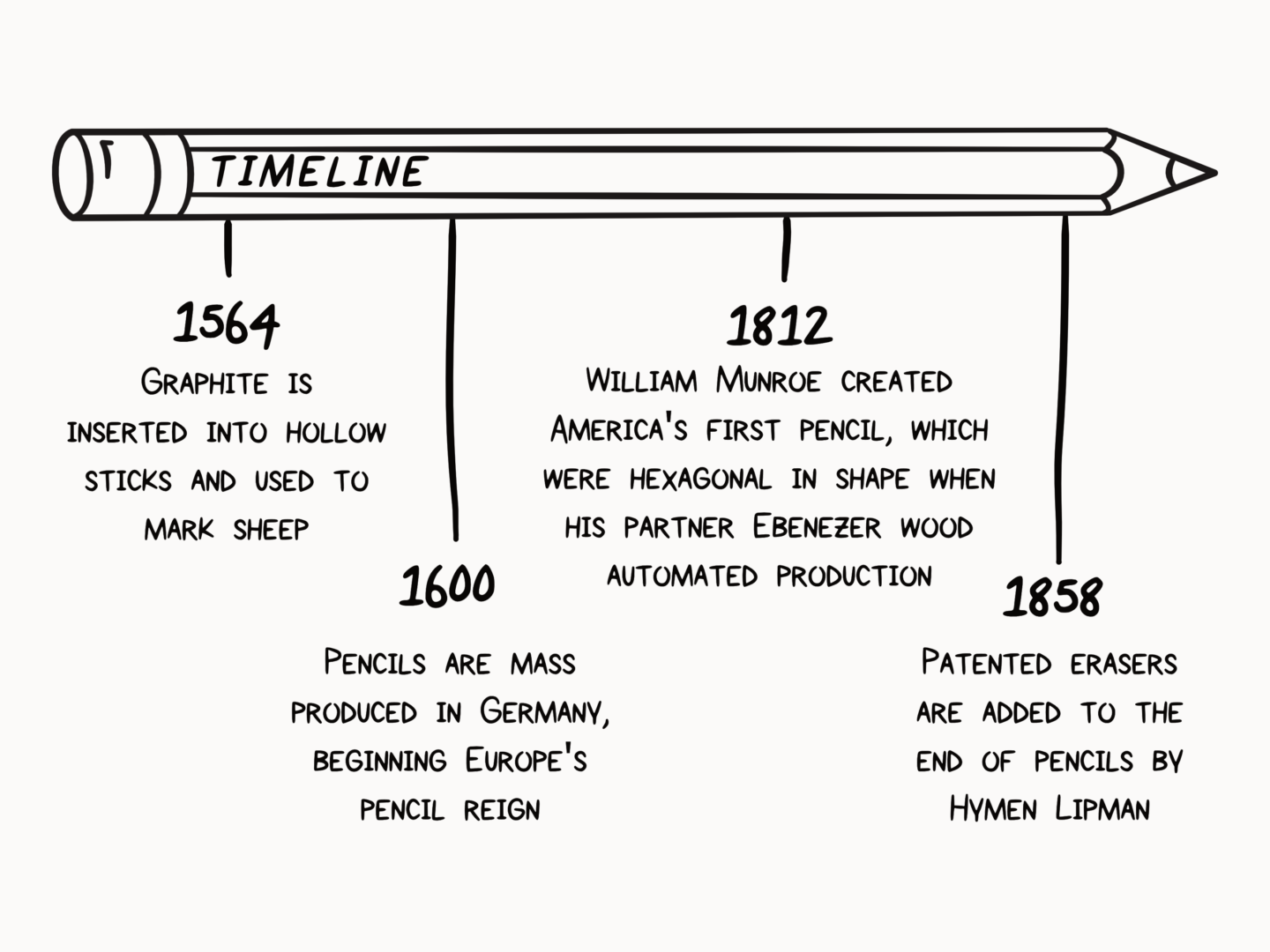

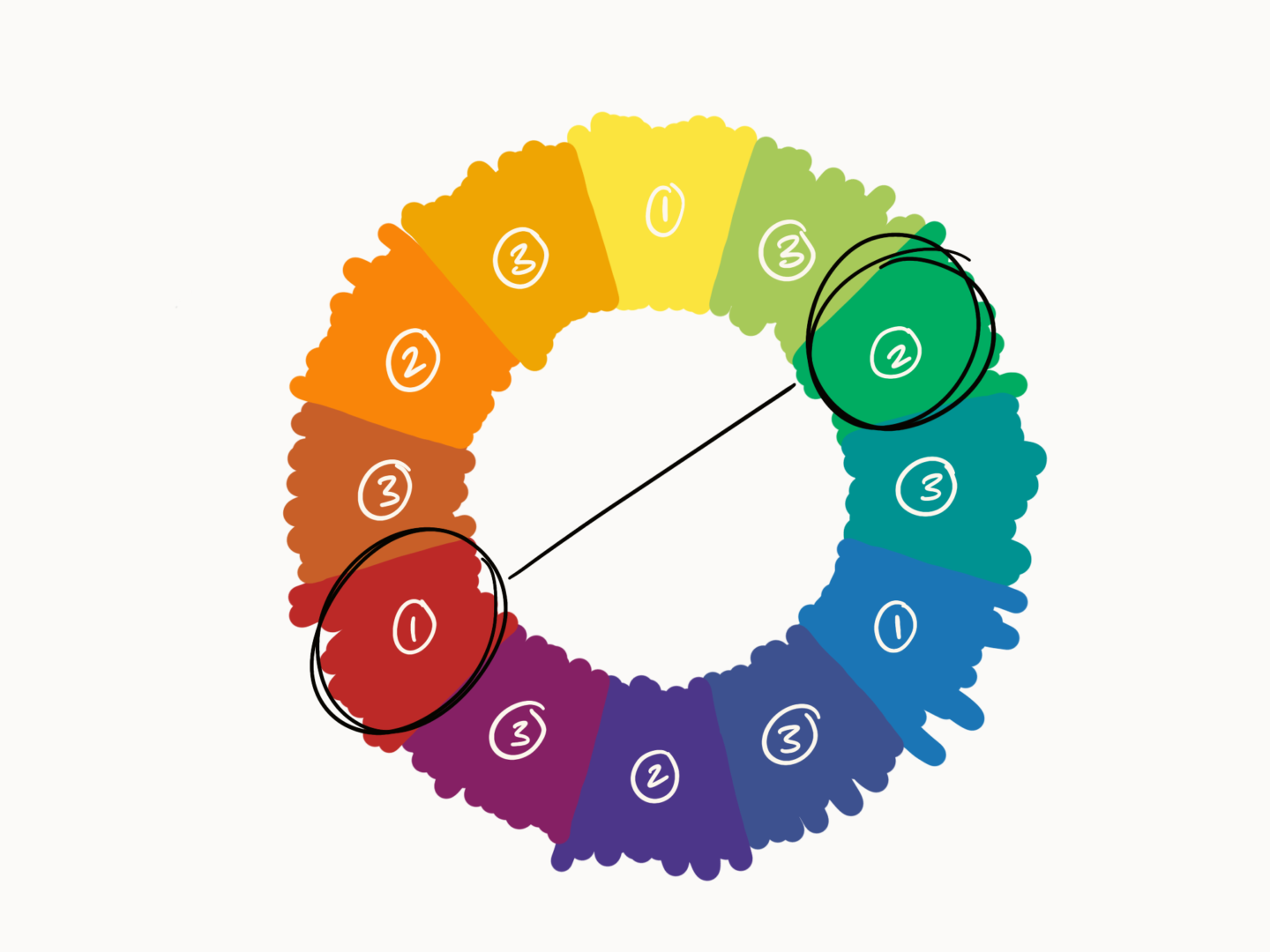

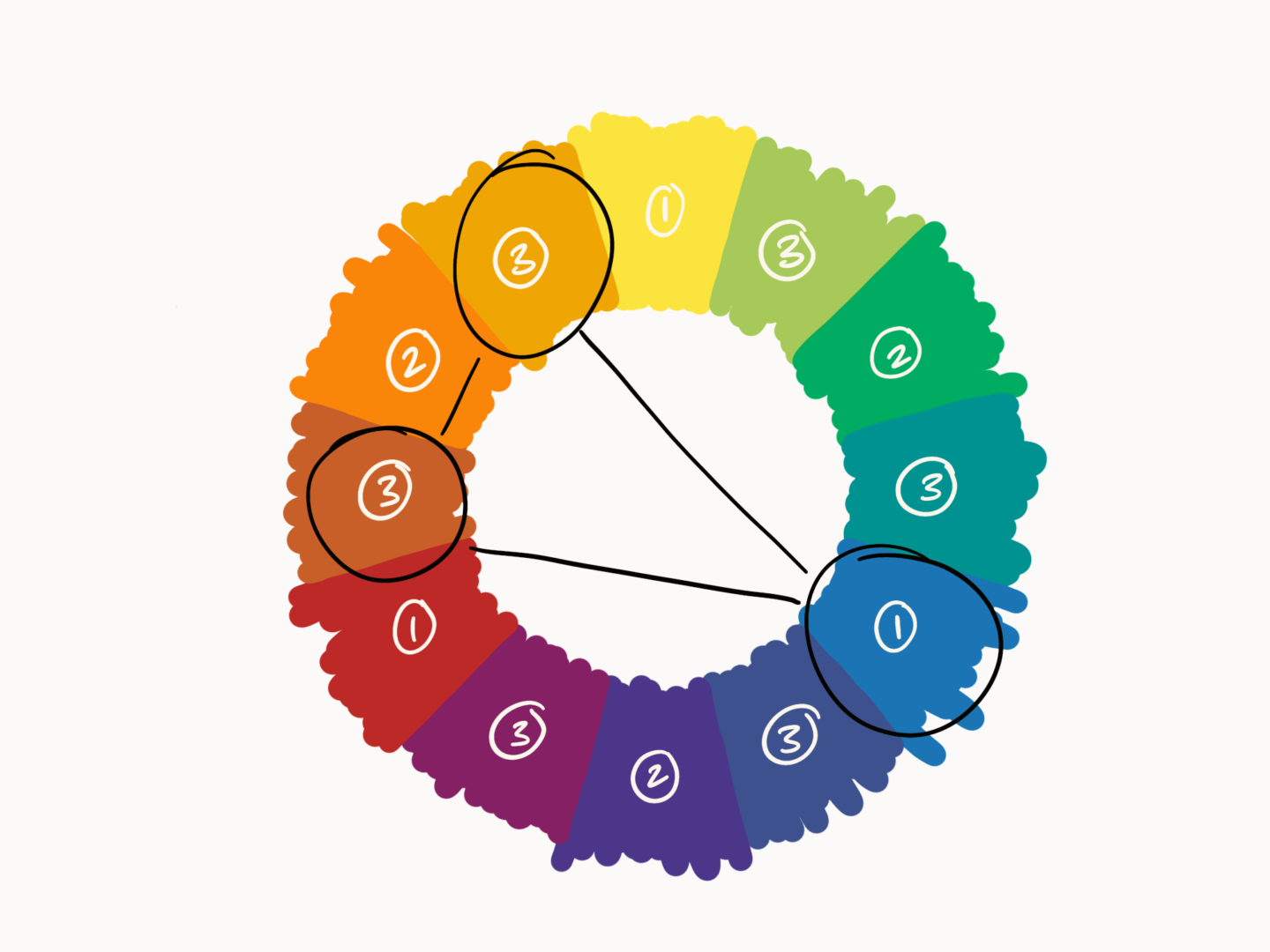

The colour wheel is the basis for pretty much everything in colour theory (example above). It’s made up of primary colours (red, yellow, blue), secondary colours between those (orange, green, purple), and tertiary colours between those (red-orange, orange-yellow, yellow-green, etc.). Colour theory offers some basic frameworks for picking colours that work together. I’ve outlined a few below, but I’d highly recommend you watch a great 6 minute Youtube video called Beginning Graphic Design: Color if this is all new to you.

Monochromatic – a colour palette which uses a single hue (colour) from the colour wheel and just plays with saturation (how vivid the colour is) and value (how light/dark the colour is)

Analogous – a colour palette based on a set of hues all close to each other on the colour wheel – a good example being the classic warm or cool palettes you see

Complementary – a colour palette which uses two opposite hues on the colour wheel for a pop – the red and green of christmas is a good example of this one

Split complementary – a colour palette which uses three hues one from one side of the colour wheel and the two adjacent to the first’s complementary colour (I made a diagram for this one because it’s hard to describe)

Using that knowledge and through some trial and error there are now really three key methods that I use to put together a colour palette:

- Analogous or monochrome with a complementary pop – The most common structure I use is to pick a few analogous hues or even a monochromatic base for the majority of my colour palette then pick out a complementary colour to add a pop. This gives you something harmonious range of colours, without it feeling too boring.

- Analogous with an accent – Sometimes using a complementary colour as a pop can feel a bit to bold, so in those cases I stick with analogous hues. I pick out four analagous colours, playing around with saturation and value but generally keeping them a little more muted. Then I pick a colour just at the edge of that range and create a brighter accent colour to use as an accent.

- From nature/photos – Then sometimes I come at it from a completely different angle. As a lot of my patterns draw from real life, I quite often use reference photos not just for the structure of my illustrations but also the colour. I have a hunt for a photo I like and then I pull out the colours I think work. This usually works particularly well with nature based images in my experience. I tend to try and pick out colours that already sit nicely together, or are natural shadows. Then I go for anything unusual that catches my eye. I usually use the Pantone studio app to help me with pulling those colours out and creating a palette I like, but there are loads and loads of tools out there you can try, or you can just do it within any digital design/illustration software you’re using with a colour pick tool.

As a rule of thumb the majority of my colour palettes are based on five colours. But you can certainly use more or less. In fact you can bend pretty much any of these methods, which is what I do all of the time, because all they’re really just guides to point you in the right direction.

If you have any top tips for putting together colour palettes or any favourite tools/sites for inspiration please do let me know! I’m always on the hunt to learn more.

Happy colouring!