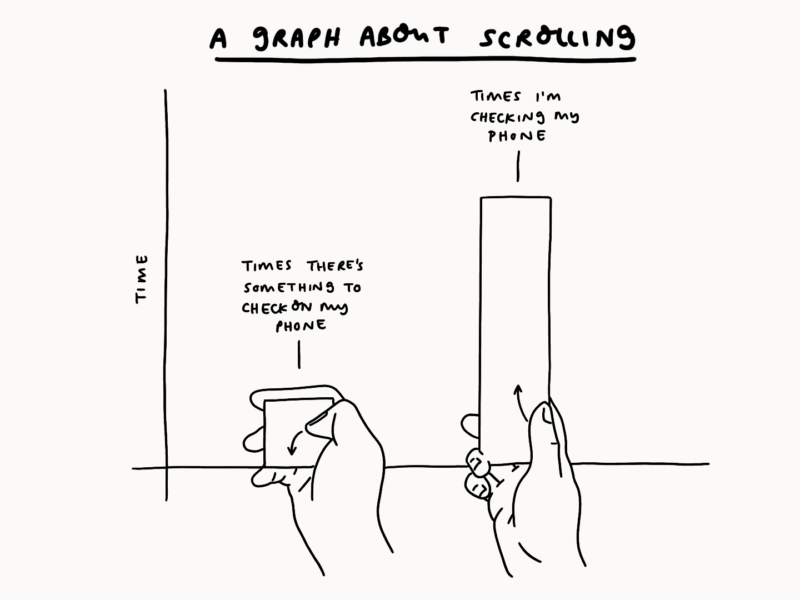

Every man and his dog and his dog’s best friend has a blog or a YouTube channel or a podcast or at least has a social media account where they share their take on the day publicly. But far gone are the days when those takes on the day are just “Natalie is eating cereal this morning. We don’t document so much as dispense now.

There’s a pressure that what we dispense online must come with a value. We crave communities or just crowds to share our lives with. You’re meant to be able to find your tribe online, or at least feel like you might be part of something more than just a person looking at a screen. But the internet today is an attention economy, and that means more often than not you have to provide a value exchange in order to get the attention of that tribe.

As we drift further apart that value exchange is less about a mutual love of breakfast foods and more about providing insight. You have to be able to teach people something or show them something completely new. You have to have that sparkling perspective. You have to have it even if you’re their peer. You have to have it even if you’re just working the thing out for yourself. You have to have those perspectives, all the time.

The concept of having to share some value in your perspective obviously isn’t new, people have written articles and books for centuries. But at this scale and frequency, where it’s baked into so much of all of our lives, it feels unprecedented.

It seems like as soon as anything newsworthy happens there’s a rush to have the trending opinion, to be the first to take a different or woke perspective on the issue. As soon as Notre Dame caught on fire twitter was awash with images and condolences. Then, before even taking a breath, it was filled with perspectives. When the Mueller report on his investigations into Trump was released, there were people claiming insight within half an hour, despite the fact that they couldn’t possibly have read, let alone digested, the document. With that same release, we also saw commentators offer live, blow by blow, page by page, tweet by tweet hot takes.

If you don’t have a perspective, you’re not seen to be engaged.

One person I follow, in a moment that has stuck with me during the last election, retweeted a lot a number of articles by political journalists and economists. She clearly had an opinion due to the lean of what she was sharing but never came out with an ‘original’ argument or declaration. She was called out for it. Why hadn’t she just come out and given her thesis on the subject if she cared so much? Her reply: ‘I’m not an expert. I want to share the information I’m using to make my decision from people who know what they’re talking about. The world doesn’t need me to try to make sense of this publicly’.

That seems like a pretty rare stance.

And it’s not just in the ‘public’ sphere or online where there seems to be increasing pressure to have an opinion. There’s now a service “that matches people willing to rent out their opinions on sports, film, TV and music to people too busy to consume pop culture.” People are paying for pop culture coaches, so because they feel the need to have a perspective so badly.

Now, none of this is new. Has anyone ever wanted to be isolated from the latest tea station (I’m using this instead of water cooler now because I can) gossip? We’ve all checked the latest scores, skimmed the headlines or crammed an article on last nights big thing before. But it seems like our thirst to have framed the world just right ahead of time, to be in the know, to have the woke perspective is ever increasing.

I don’t know how we break out of this, or if we will. Sometimes I think the answer is to stop sharing altogether. Sometimes I think it’s about sharing differently. Most times I think it’s a symptom of much greater cultural forces which are at play.

So, for now, I’m just going to do what feels right in the moment.

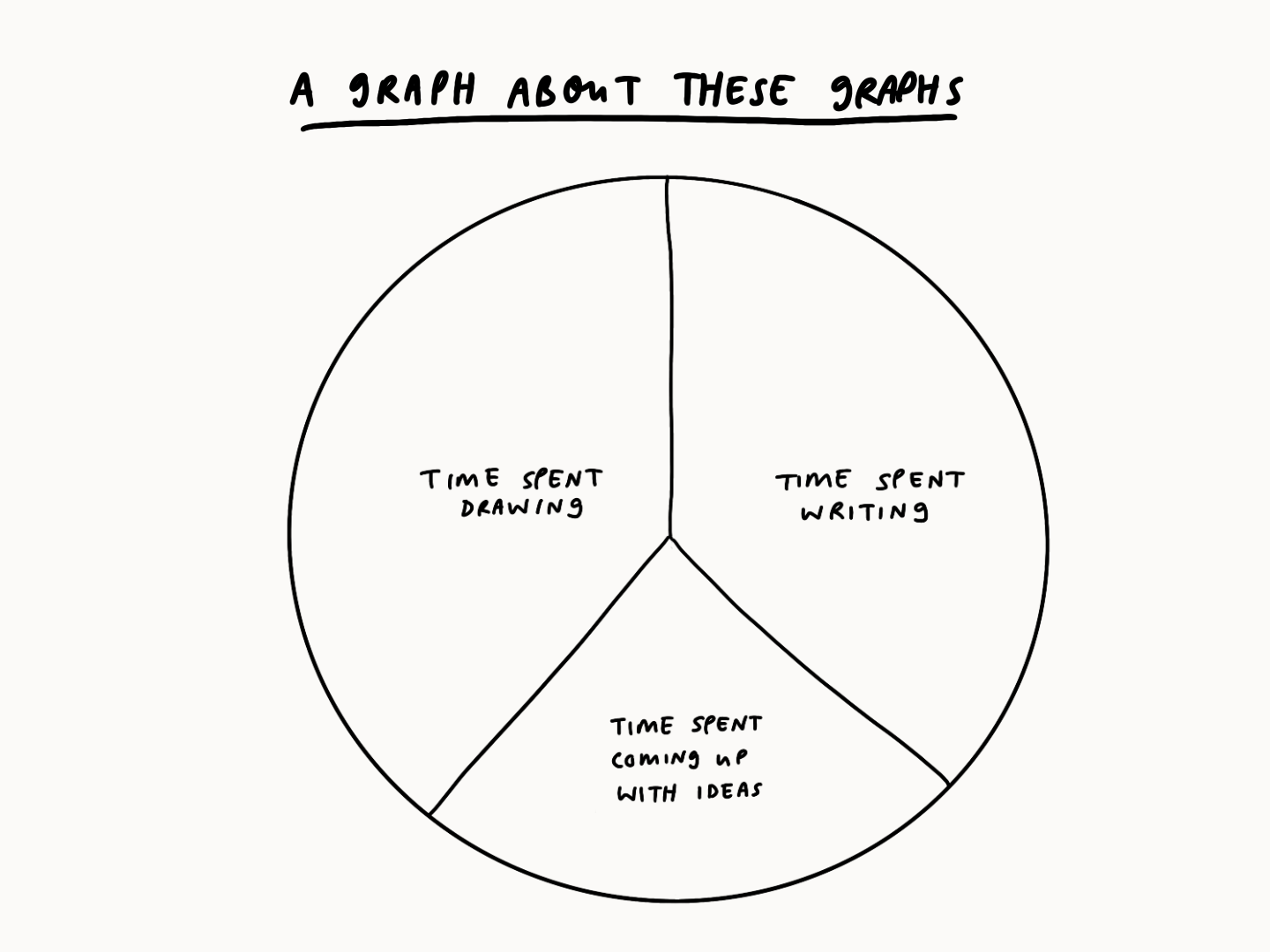

While I’m writing about perspective, I also want to address the fact that the tone of this space, this blog has been shifting recently. I’ve been giving more weight to ‘think’ style pieces because topics like embracing uncertainty have been on my mind. These baby essays had been reserved for my newsletter, but they’re some of the pieces I enjoy writing the most and that gives me the most reward. There’s something powerful in sitting down to work out your thoughts on something tricky, to try to structure them, before you open them up as dinner table fodder. I guess it’s the naval gazing version of framing the world just right ahead of time. I am an anxious bear after all.

I’d been reluctant to share those kinds of perspectives here because they felt self-indulgent or even self-aggrandising. I’ve sat uncomfortably with the idea of this blog having a (tiny) audience since the start. I write, illustrate and research what I want first, always. But it’s incredibly difficult not think about who might read whatever I come up with, how it might be received and if it has the potential to support my other work – often people find me for commissions through this blog or my social media.

If you will allow me a metaphor, the way I picture it is this: creating content online is a bit like being a busker. You’re performing as people pass by. Now you can perform in order to try to catch their attention for a split second, to turn them into fans. You can listen out for the things people cheer for and build on them. You can pay attention to their reactions and grow with that audience. Or you can just play what you like. You can close your eyes and not notice who stops, you can make the active choice to keep playing no matter the reaction. With you blindfolded, it’s something of a schrodingers audience. Or you can perform what you like with your eyes wide open and learn to keep going no matter what happens around you. That requires wither some incredible expectation management or some even more incredible self-confidence.

I’m trying to keep making what I want no matter who’s on the street. I’m trying to be slower with my perspectives, taking time to orient myself and take a good old look around first not at an audience but at the world around me. I want to be anthropological about it, to be in the study but not its subject.

But, as ever, we’ll see. As much as I try to frame them, my perspectives are always changing.

I recognise the irony of this piece. I’m questioning whether we need to have an opinion, a public opinion with a sense of authority while writing an opinion piece on my blog. But as Alanis Morisette said “It’s the good advice that you just didn’t take / Who would’ve thought, it figures”

Natalie