I have a difficult relationship with my inbox.

Getting my first email address, one that was named after a fandom, felt like a key to the world of the internet. It allowed me to do so much and it let me stay in touch with friends. But since then, that key hasn’t opened doors; it’s locked me in.

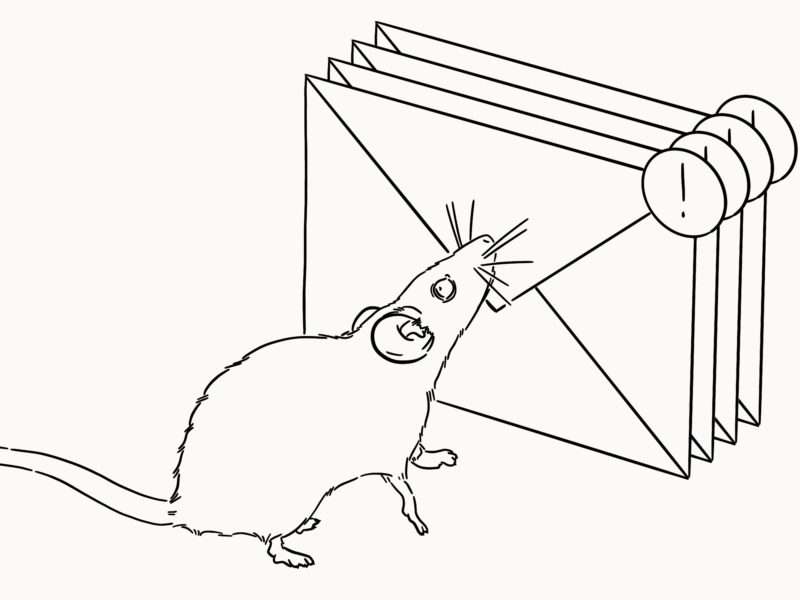

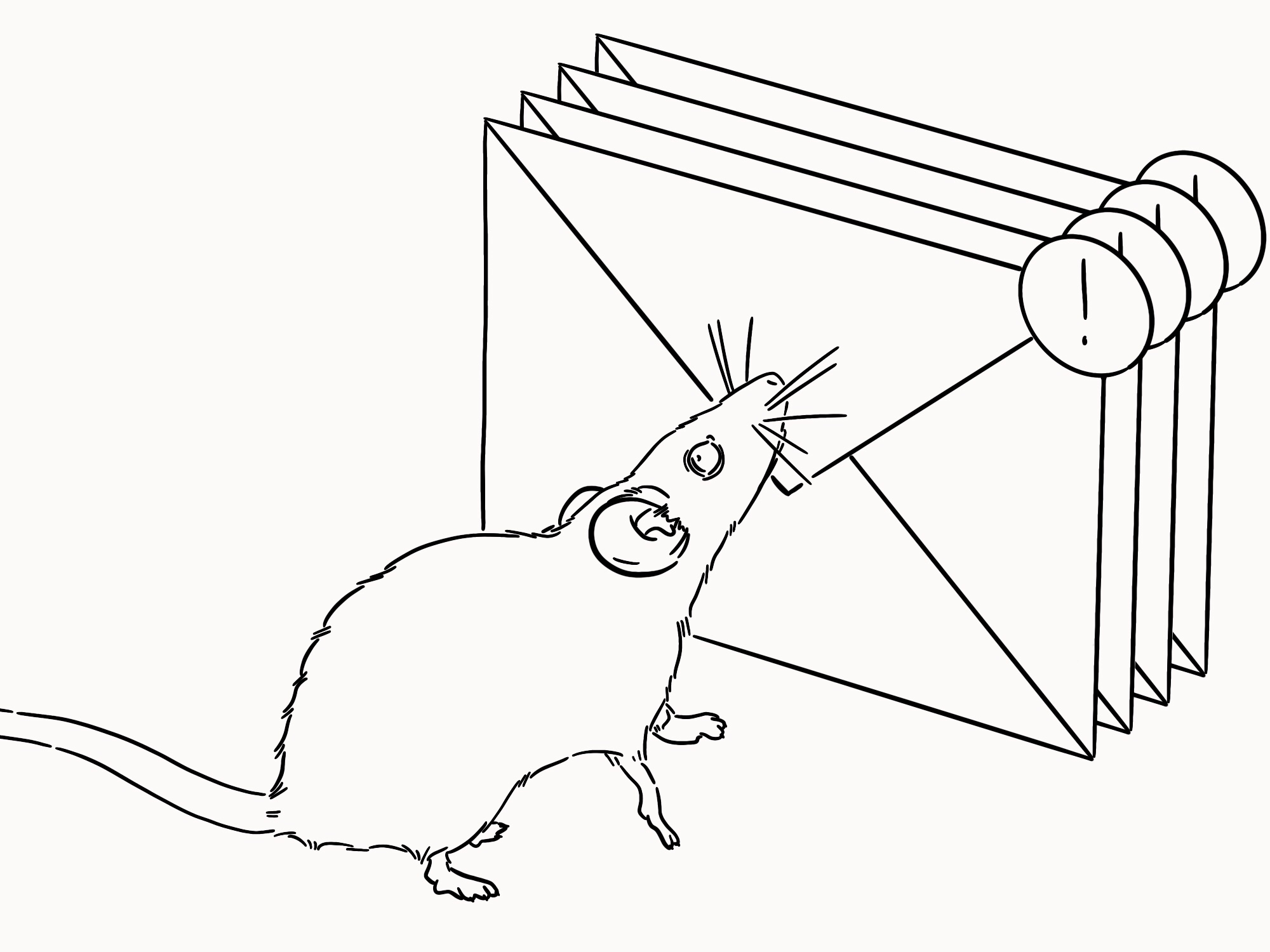

Before we jump into my relationship with email, I want to set up a bit of scientific context. Specifically, I want to talk about B.F. Skinner’s operant conditioning experiments. In these experiments, Skinner famously conditioned rats to learn that when they pressed a button food would be dispensed. But after the rats had learned to press the button, further experiments were done. The button was changed so that it didn’t dispense food every time it was pressed, but rather at irregular intervals. The result was that the rats pressed the button more frequently than when the food came at every push.

When it comes to social media and email we are like those rats. We’ve been conditioned to keep hitting refresh for a reward, in the form of likes, comments or contact, that may or may not come.

It became less about the content and more about a constant search for the next dopamine hit. I was playing a fruit machine but instead of a flush of cherries I was getting spam from companies I didn’t care about. I refreshed indiscriminately, in any moment of quiet or anxiety.

This wasn’t the world of romantic opportunity we hoped for in You’ve Got Mail. It wasn’t even the efficiency of communication that it had promised in our work. I was a full on email junkie.

I want to start breaking the habit, the addiction.

My first thought was to go cold turkey. I could probably have managed it for social media, but unlike the people you read about who are able to leave email behind (often because they have assistants or as part of their role as journalists) I’m not in a position to turn my back on email. I also realised that any break, even if I could get away for a week or two, would be temporary. You could sober me up but then as soon as I was back I’d be walking through a digital liquor store every day.

So instead of completely cutting myself off from my email, I decided to try to reshape my relationship with it. I wanted to take myself out of the operant conditioning chamber.

My first step was to remove the email apps from as many of my devices as I could. Everything personal is now done through the web. That puts one barrier between me and the fruit machine. It also means I get no notifications.

I’ve kept my work emails on my work laptop, because it’s part of what I’m paid for, and I’ve kept my work inbox on my phone. But where I’ve had to keep the apps I’ve turned off all notifications, including that little ticking red box that counts all of your unread emails, taunting you with them.

My next step was to set up a new address, one that was just for people.

This new, more professional email address, gave me two things. First, it brought me clarity. There was no spam, no more constant cycle of emails, no clutter. Second, it had a side benefit of giving me a digital channel I was proud to use to communicate with the world. I’m in the process of growing up online and this felt like finally stepping out of my school uniform.

The final step I took was choosing scheduled times to check my email.

Rather than checking whenever I felt the itch, whenever I had a moment of boredom, whenever I felt a glint of anxiety that could only be dulled by shine of a message to remind me I was here and in demand enough to be worthy.

Since making those changes, I’ve felt my relationship with my inbox become healthier. I’ve been less distracted. I’ve not missed anything important either. I don’t owe anyone an immediate response, and I don’t work in the burning building business so it can all wait until I’m ready.

It’s a change that’s still in progress. I’ve still not managed to fully kick the habit, and I’ve not even started on social media yet. But it’s all about those baby steps.

I’m not a mouse. I’m a woman and I choose the conditions of my own experiments.