Earlier this year, back when we could travel and be in rooms with other people I went to (and spoke at!) Service Design in Government Conference. I had an incredible time, and left feeling more determined and inspired than I’d felt in a long while. There was something in the idea of taking a step back and consequence scanning what we do, to ensure the impacts of our work butterfly out positively. There was also something in hearing about the personal work, and provocations, people had felt compelled to undertake whether that was baking cake or creating environmental service standards.

I knew I wanted to commit to doing more meaningful personal work and reconnect with the manifesto I wrote for my work when I turned 26, because as much as I’d always believed in those values I hadn’t been actively living them.

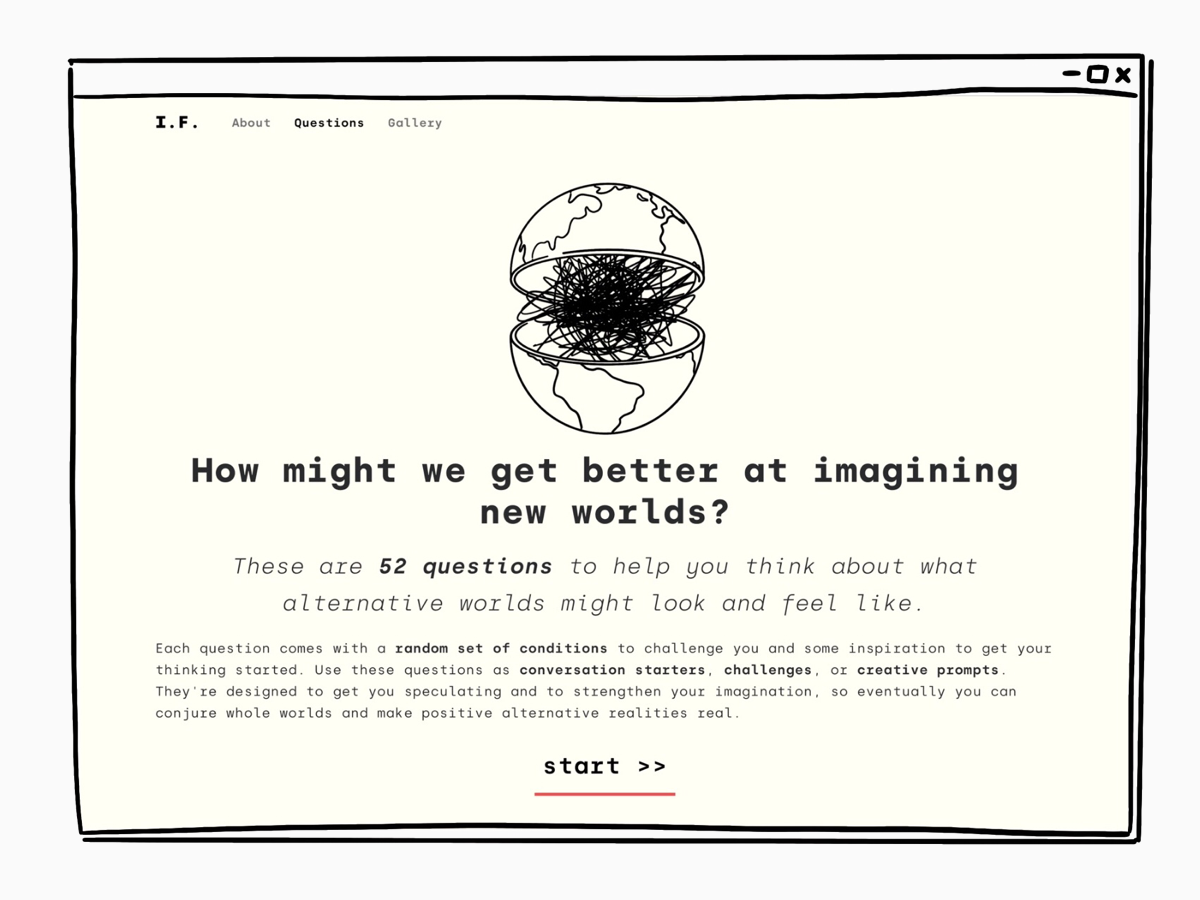

Imagining Future Spaces is my first attempt at a first attempt at that.

Imagining Future Spaces was an idea I had in response to two moments. The first was a talk by the incredible Cassie Robinson where she asked “what has happened to our imaginations?” and advocated for social dreaming. The second was a series of conversations I had with friends and loved ones while we were on the brink of COVID-19 where despite seeing the effects take hold elsewhere, we couldn’t describe what impact a lockdown would have on our days let alone what a life post-pandemic might be like.

There are likely hundreds of complex and interwoven reasons why our imaginations appear to be weakening, or at least appear to be able to imagine themselves out of the status quo in anything other than a dystopian horror.

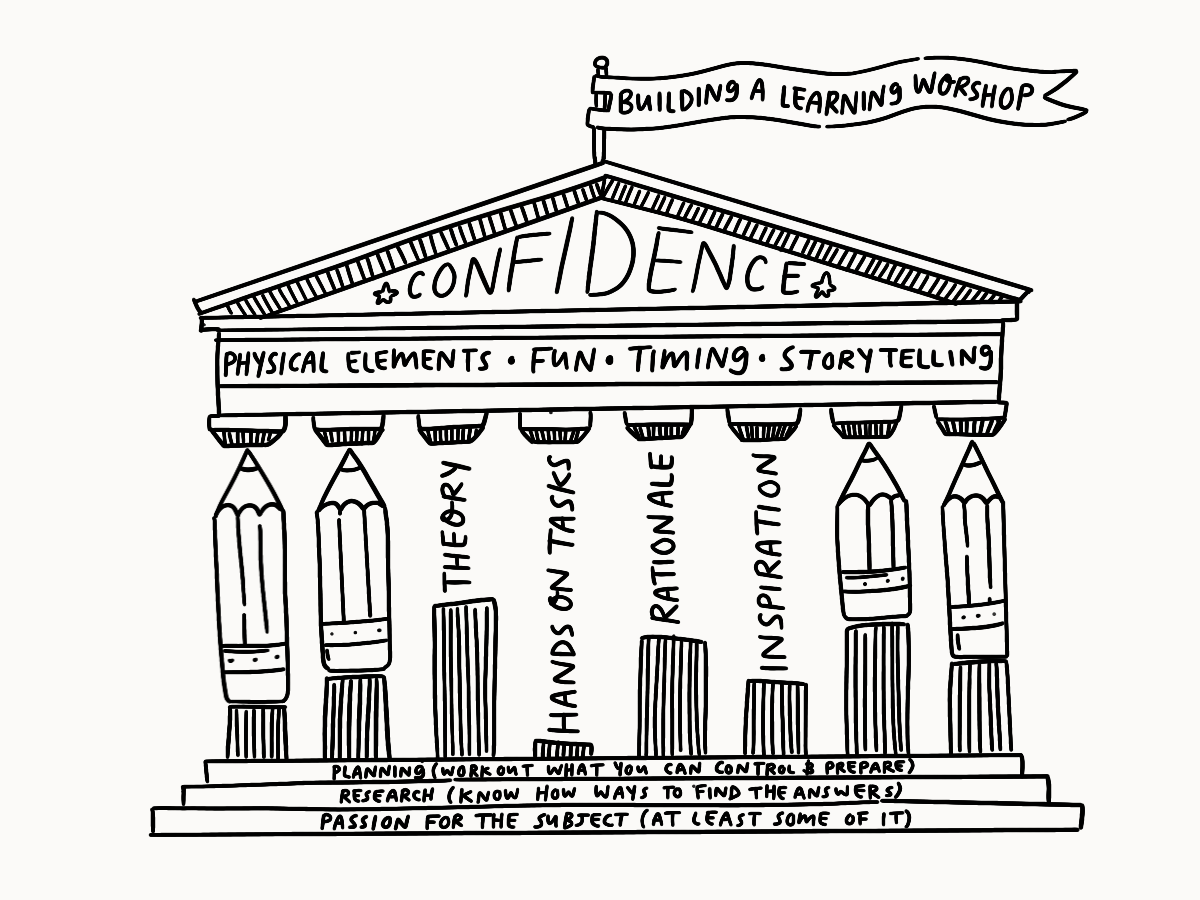

But one thing I have always believed to be true is that you can get better at anything if you commit to practising. So I thought I’d put my skills as a researcher and illustrator (AKA I like questions and weird juxtapositions) to use and create a space to practise.

That’s where the 52 questions that make up Imagining Future Space came from. There’s one for every day of the year or card in a deck. There are just enough to create sustained practise and or a space for play.

Learning from the questions posed by Aron, Melinat, Aron, Vallone and Bator in The Experimental Generation of Interpersonal Closeness, better known as the 36 Questions that lead to love, these questions get more personal and more abstract as they go. They’re designed to be a challenge. They cover small tactile things like what’s in your pockets, to more social questions about our relationships as well as bigger questions about how we’ll stay fed and healthy. I tried to make sure I asked about a wide range of subject and kept the questions as open to a wide range of responses as I could. But they do only offer imaginary snapshots of what alternative worlds could look and feel like. In order to truly imagine and design sustainable new worlds, we need to think in systems, but that’s a challenge bigger than today.

Each question comes with a random set of three conditions (some realistic, some silly) to challenge your imagination but also take away the fear of a blank page. The “in world where” offers some environmental, social and value based context that hopefully offers just enough of a push out of the everyday to lead people to think about alternative possibilities.

There were moments where it felt self-indulgent to start a project like this. Who am I to create and curate a space like this? But after a while I reconciled myself with that feeling, imagining the future is work for everyone. Even if it is self-indulgent, I learned a lot making it and I think I’m going to continue to learn a lot through using it.

Whether it was writing the questions, creating 54 illustrations that were aimed to inspire fun and lateral thinking in responses, or building the site in wordpress, reviving my tiny bit of coding knowledge, putting the thing together reaffirmed to me that this is the kind of personal work I want to be making. The complexity of the project challenged me in a way I haven’t challenged myself in a while.

The first launch of the site is only a starting point though. I’ll be adding more creative thinking tools to try to make the process as supported as possible. I also want to draw on my anthropology studies at Goldsmiths and add some context to each question to show how different societies are currently creating their own alternative worlds whether that’s through how they organise themselves, their environments or their values.

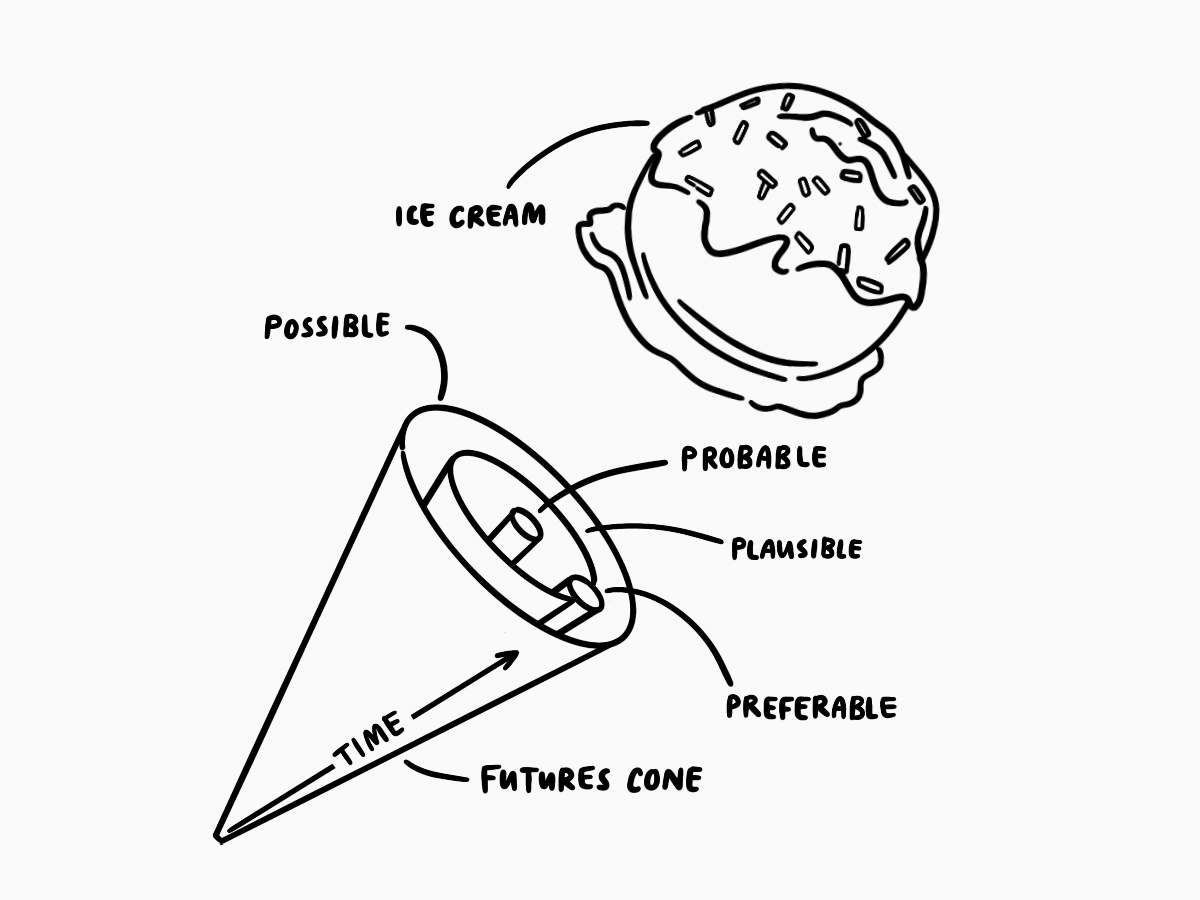

Over the next year I will be trying to create my own responses to each of the questions. I’ll be challenging myself to think of what’s possible, not just what’s probable or plausible.

I’m hoping other people join me and share their ideas for what alternative worlds might be. They might discuss, draw or describe whatever it is they’re imagining, because the more you make your ideas tangible, the easier it is to start to speculate about and imagine more complex alternatives like what new ways of life might be like.

Imagining and creating the future needs us all to get involved.

I’d like to imagine a world where we can develop stronger imaginations together and through doing so gain confidence in our own potential and the potential for alternative worlds to exist.

I’d like to imagine a world where perhaps we might even get to take that belief back into the present and push for positive changes to the world we’re in and shaping all of the time.

I’d like to imagine a world where fingers crossed there will be ice cream too.