Design thinking is a concept that I hear bounced around a lot at work and in a lot of the articles I read. It seems to be the buzz word du jour, to go along with a growing interest in Service Design. This interest isn’t about aesthetics or logos. It’s about embracing the principles of design as a process in the way people work.

So, what is design thinking? First off, it’s more than just buzz. Design thinking is all about taking a user-centric approach to a problem and then solving it in a hands-on iterative way. By focusing on the real user, and empathising with them, you are able to build something they actually need, rather than what you think they need. Taking this insight and working with it iteratively, prototyping and testing means you fail small and often as part of a process rather than dedicating a huge amount of time and resources to a project that might have an underlying flaw you hadn’t noticed. This process can take slightly longer at first, but it becomes more time and energy efficient overall because you work out more of the kinks at the start.

Design thinking isn’t just for designers or businesses. It can be used by everyone and anyone who’s creating something or grappling with a big question because its process is so simple and can be flexible around whatever you’re working on.

“But how?” you ask.

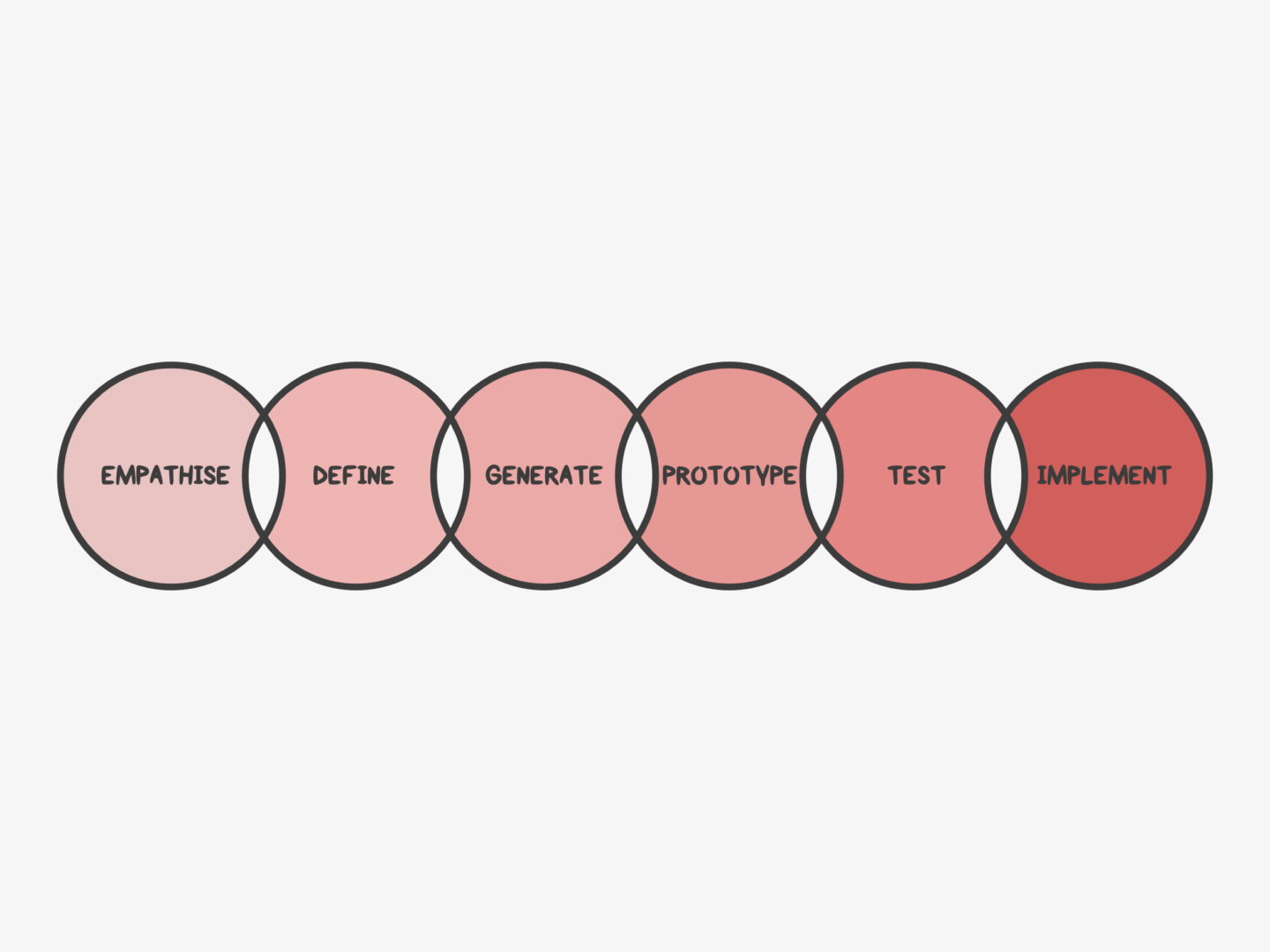

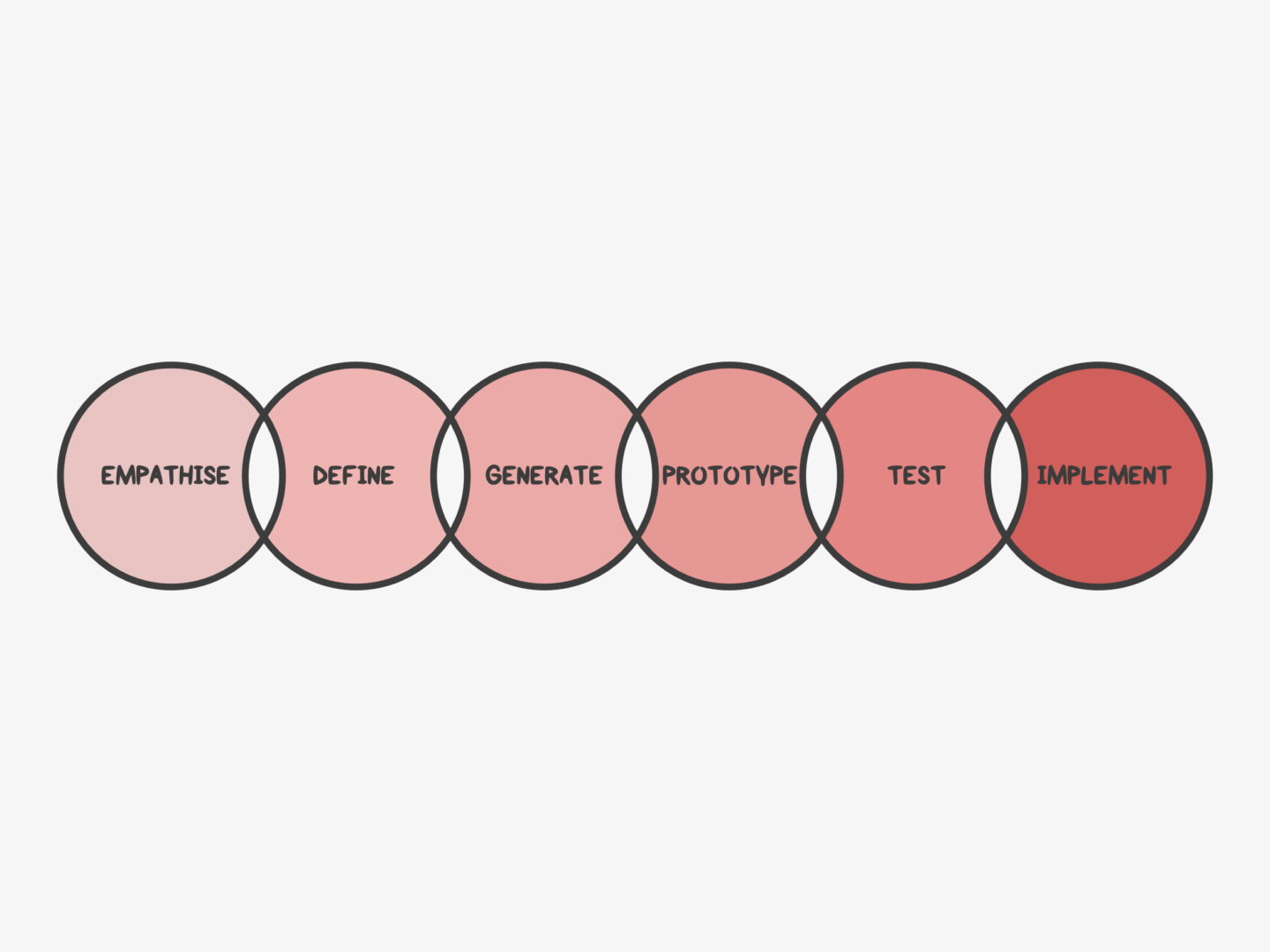

Well, the design process goes a roughly a little something like this:

EMPATHISE

Step one is all about understanding your audience or your user. This involves actually speaking to them, rather than just imagining what they think, or feel, or do. Where possible observe what they do in the space you’re looking to get into, so you can find the problems they face and the motivations that drive them. In order to be able to empathise with them and build for them, you need to understand them,

DEFINE

Researching and observing your target audience normally leaves you with a lot of information, so the next step is to hone that information into just a few golden nuggets of insight. You can do this by, once again, empathising with your audience to find out what they care about the most and what experiences or pain points they share.

GENERATE

Once you’ve focused your research on a couple of key points, you need to start coming up with solutions the problems you’ve identified, lots of them. At this stage, you need to generate as many ideas as you can, no matter how wild or unfeasible because you might be able to take something from them. Where possible do this in a team, so you can bounce ideas around and build on each other’s thoughts.

PROTOTYPE

Then you want to build rough models of your favourite ideas. You want these prototypes to be as tangible as you can make them. If you’re building a website, put together some wireframes. If you’re making a board game, build a mini version out of card. If you’re developing a menu, get cooking. This is where you find out which ones are most likely to work or be doable.

TEST

After building your prototypes you need to test them, on your target audience where possible. Get their feedback, you’d be surprised at how often something you think is as simple as ABC is completely indecipherable to a stranger. Take their feedback and then work it back into your prototype. Lather. Rinse. Repeat.

IMPLEMENT

Putting what you’ve built into the world, and into practice, is the last step. Make sure all of your learning comes together in a form that’s accessible to your audience and does actually solve their original problem. There’s no point creating self-cleaning glasses (please someone create these) if they’re not accessible or marketed to glasses wearers.

And that’s it. Apply these principles as you will!

If you’re interested in reading more about design thinking, I’d recommend having a read of some of the articles from The Harvard Business Review’s edition all about it or checking out This is Service Design Thinking which is at once thorough and accessible.

Natalie

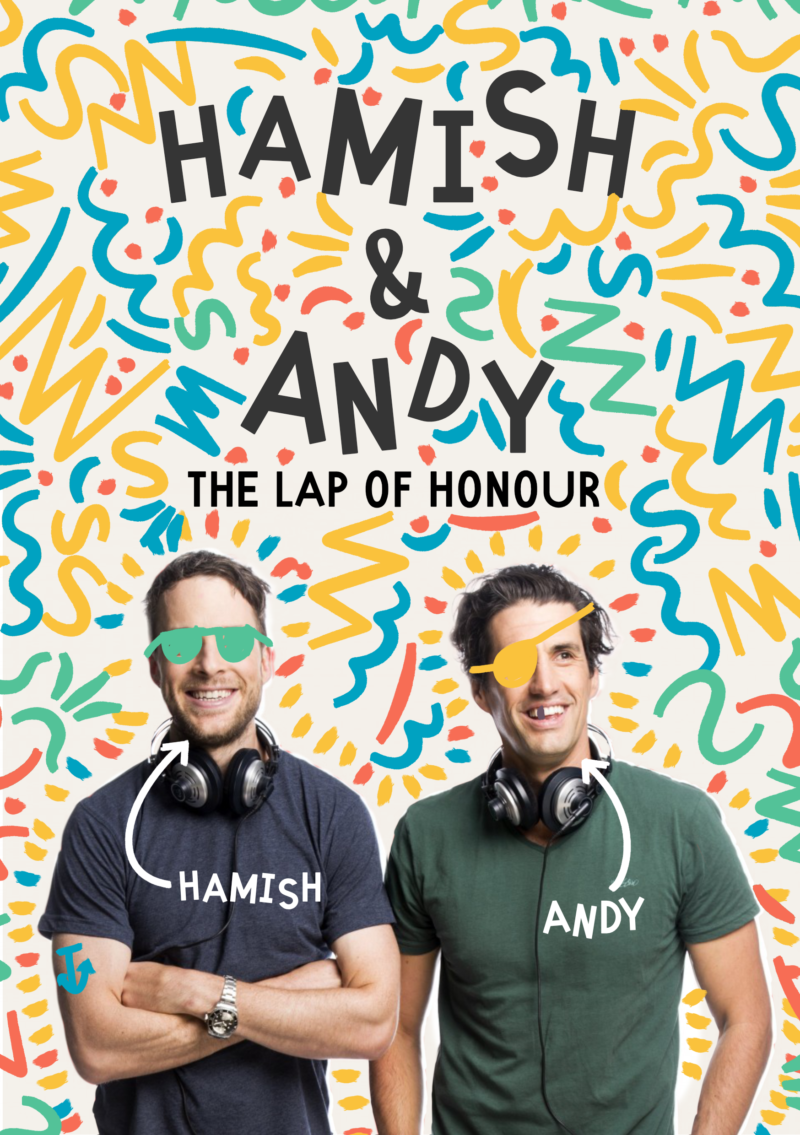

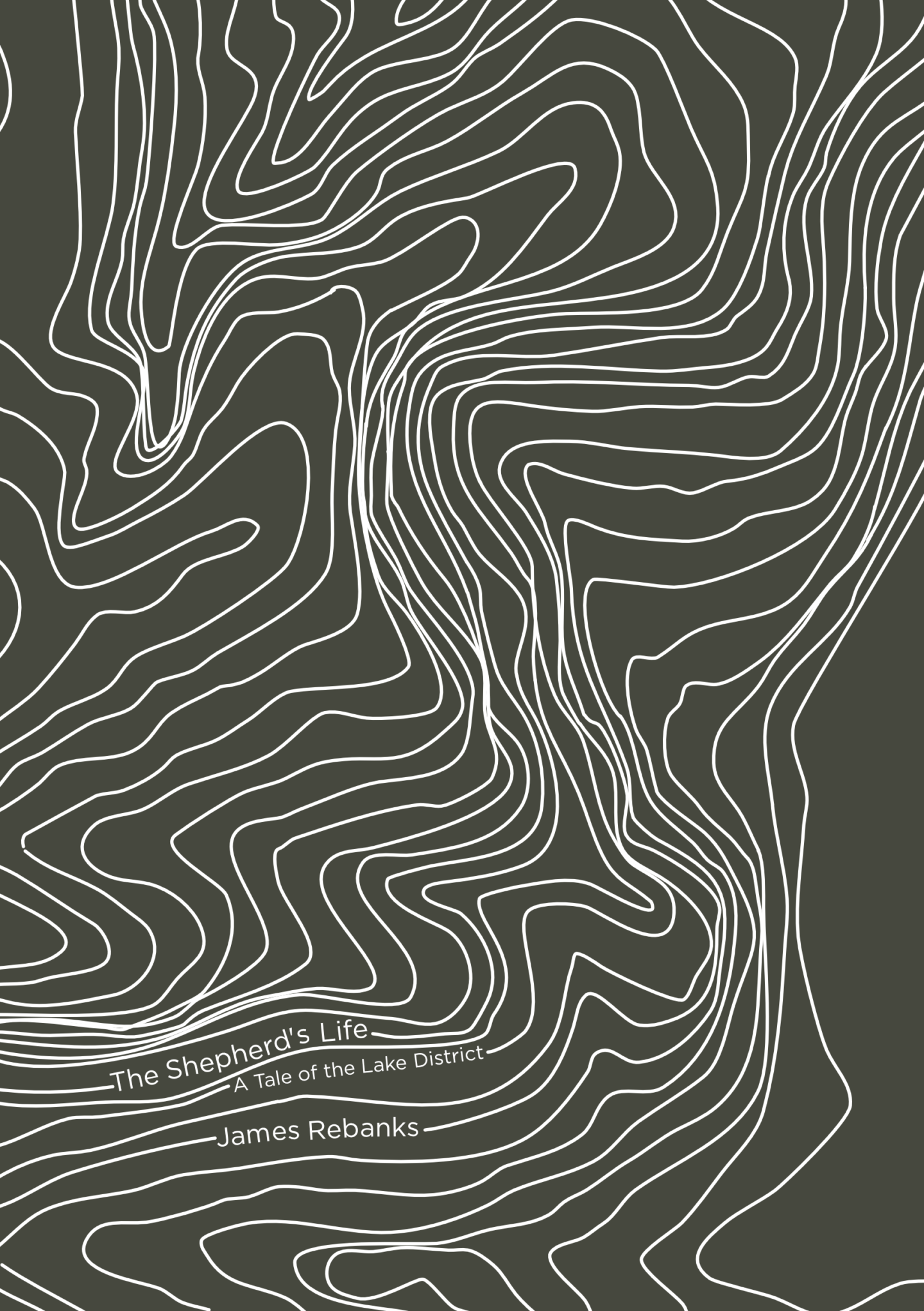

A common way for designers to hone (and often show off) their skills is to redesign their favourite movie posters. People like Peter Majarich have created some incredible alternative designs, that really capture something about the film that’s at the heart of their work. Inspired by those posters, I decided I wanted to do something similar.

A common way for designers to hone (and often show off) their skills is to redesign their favourite movie posters. People like Peter Majarich have created some incredible alternative designs, that really capture something about the film that’s at the heart of their work. Inspired by those posters, I decided I wanted to do something similar.

SOME QUESTIONS TO PONDER AS YOU READ

SOME QUESTIONS TO PONDER AS YOU READ