This is a much overdue design story. The graphite pencil is the ultimate everyday design essential, the tool that launched 10,000 masterpieces. But it has been much neglected in this series, up until now.

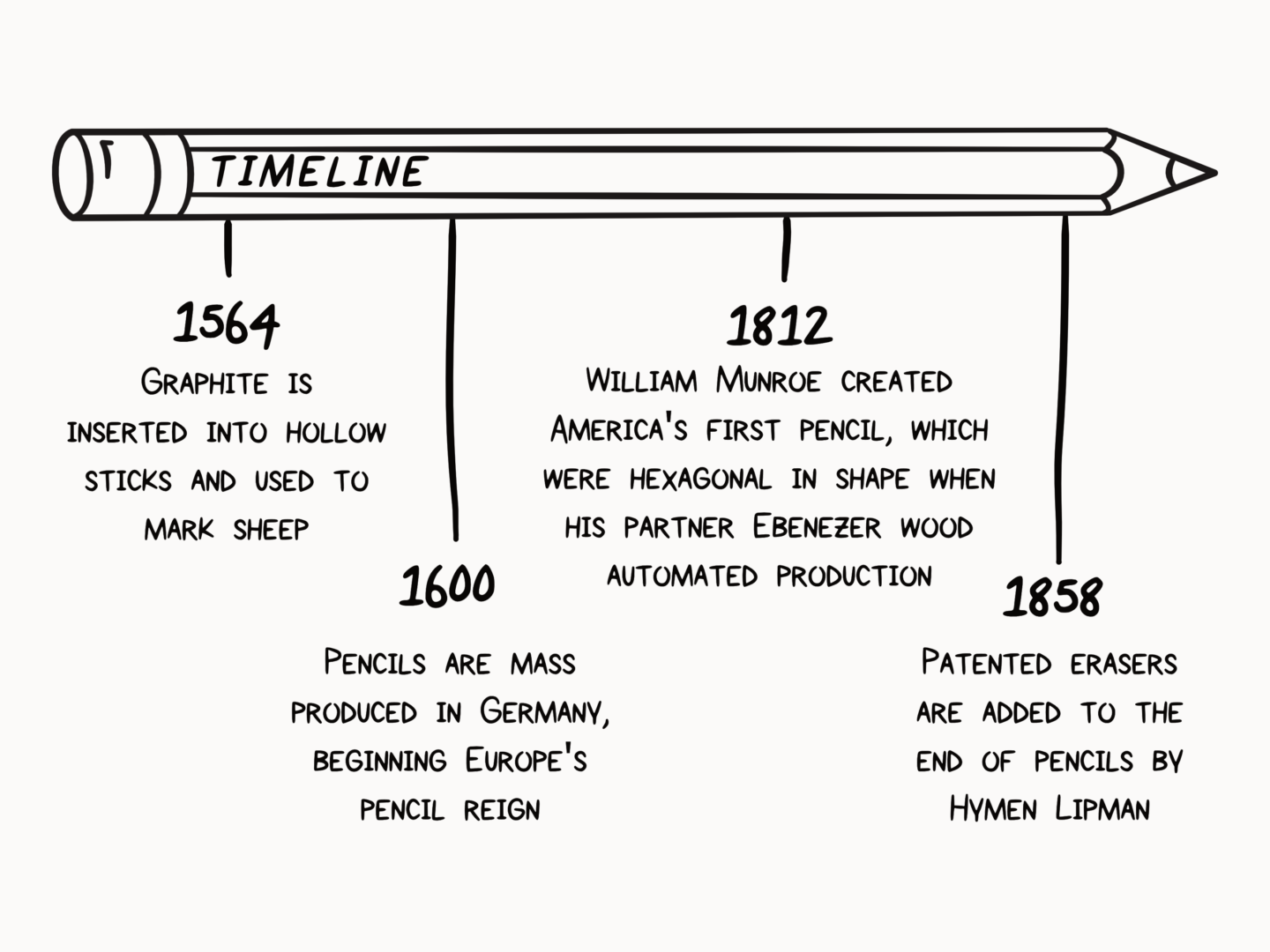

As you might have guessed the story of the pencil starts way-way-way back. In fact, it goes back to the early 1500s when the first major deposit of graphite was found in Grey Knotts of Seathwaite in Cumbria, England. Where the pure material was carved up into sticks and used by local farmers to mark their sheep – denoting their ownership and making them easier to separate on the hillside.

From this first agricultural use, the graphite transitioned into use as a writing implement. It also spread across the continent. By the end of the 16th Century graphite was preferred to charcoal and lead throughout Europe because of its “superior line-making qualities, its eraseability, and the ability to re-draw on top of it with ink”.

That “eraseability” wasn’t quite what we would think of now though. The original erasers were actually just stale ends of bread – we once had to use crust erasers in art class and I can confirm they work. The move away from bread, was made by accident in France, when a writer accidentally picked up caoutchouc—a stretchy sample of the newly-discovered Para tree – instead of his erasing baguette. It wasn’t until 1858, some 300 years after the first pencils, that the American Hymen Lipman came up with the idea of adding a rubber eraser to the end of a wooden pencil. His first patent included the eraser set inside the wood of the pencil like the graphite, just at the other end.

But before we got to that version of the pencil went through many incarnations. As the graphite started to gain popularity in the 1560s an Italian power couple, Simonio and Lyndiana Bernacotti, devised the first plan for a wooden pencil. Before then the graphite was wrapped in sheepskin to keep the user hands clean and the soft carbon substance intact. These first designs had the wooden case, at that time made of juniper, hollowed out and the graphite pushed through the flattened cylinder. Soon after the Bernacotti’s developed their wooden pencil, a far superior method of sandwiching the lead between two pieces of wood and then glueing the pieces together was developed. That’s pretty much how we still made them now.

As with all great designs, the wooden pencil spawned knock-offs. Con artists, known as stümplers, were inspired by the high price pencils were fetching to sharpen then colour in the ends of sticks and sell them as pencils, causing frustration across Europe.

With a well-defined process in place for making wooden pencils, they began to be mass produced in Nuremberg, Germany, in the 1660s. Instead of the solid sticks of graphite used in the first pencils, the ones being produced in Nuremberg were made from a powdered version of the substance, which was mixed with sulphur and antimony before being reconstructed within the wooden frame. This mixture reduced the waste and cost of making pencils.

That mix was perfected by Jaques Conté in 1795. During the Napoleonic war, British and German pencils were in short supply in France. But the French army still needed pencils. So Conté devised a way of mixing the powdered graphite they did have with clay and then firing it in a kiln to resolidify the mixture. This process was the same one being developed in parallel by Joseph Hardtmuth the creator of the famous Koh-i-nor.

Once the production of this graphite mixture had been settled, there were only a few stages left before the pencils being created became the ones we know, love and use today. William Munroe created America’s first pencil, which was made in the hexagonal shape that’s so common today when his partner Ebenezer wood automated production. Pencils then gained their yellow colour in the 1800s when Western pencil tycoons wanted their customers to know their pencils were filled with top-quality lead, so they painted their instruments in the colour associated with Chinese royalty: yellow.

Centuries later, we’re still manufacturing and sharpening down millions of them. Remember how much history you’re holding the next time you’re starting to sketch or draft.